CREEPY VICTORIANS

- 31 October 2017

- Sofia Roberts

If you’ve visited Katherine Mansfield House & Garden and found it a bit creepy, don’t worry – you’re not alone. Visitors often comment on the creaking floorboards, possessed-looking dolls, and solemn family photographs. There’s something specific about historic Victorian homes that modern visitors find slightly unnerving. But why is that, and why are so many aspects of the Victorian life now associated with creepiness?

While death is obviously not something confined to a specific time period, it was very much at the forefront of public consciousness during the Victorian period. Sweeping bouts of sickness were a concern in both England and New Zealand. Redmer Yska details the extent of disease’s grip on Wellington in his new book, A Strange Beautiful Excitement:

“as waste filled up the ditches and piled around the harbour, the funerals began. In 1885, 63 locals, mostly in Te Aro, sickened and died from acute infectious diseases, including typhoid, diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles, and even cholera.”

Historian Stephanie Carroll correctly says that “today, we have removed death from our homes and from our minds in many ways. For the Victorians, death was right in their faces.” No one was exempt from this horror.

Image: Queen Victoria, c.1870, in mourning. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Most famously, Queen Victoria lost her beloved husband Albert, a death that would launch the British Empire into an extended period of mourning. The prolonged and intense mourning of the head of state set a standard for citizens to copy. It became fashionable to adopt elaborate mourning fashion and jewellery after the death of a loved one. The most severe mourning rituals applied to female widows, who who were required to wear full black mourning for two years – non-reflective black paramatta and crêpe for the first year of deepest mourning, followed by nine months of dullish black silk, heavily trimmed with crêpe, and then three months when crêpe was discarded. This was multi purpose: tying the wife’s identity to their deceased husband, symbolising her renewed singleness and signalling her loss to promote community sympathy. Mourning rituals differed depending on how close one was to the deceased. They were significantly looser for men, and towards the late-Victorian period loosened for women also, partially due to the extreme cost of sourcing a mourning wardrobe.

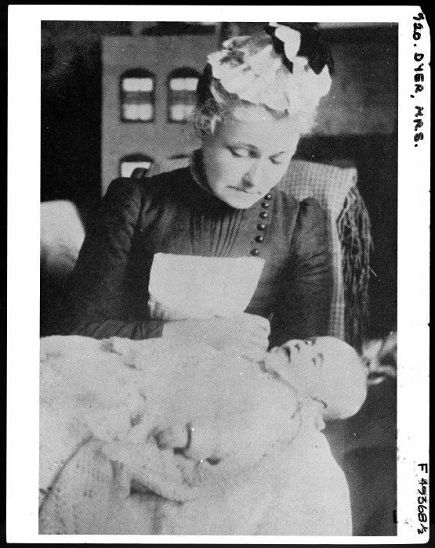

As well as fashion, death photography became a popular way or preserving the image of a deceased loved one. This saw family photographs in which dead family members were dressed and included as if they were living. Our museum includes one of these – a photo of Katherine’s sister Gwendoline who died in infancy.

Image: Margaret Dyer (Katherine Mansfield’s grandmother) and Gwendoline Beauchamp (Katherine Mansfield’s sister, deceased in photo), 1891. Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-5124-1-01.

An article in The Guardian on Victorian ghost stories posits another aspect of influence: the urban migration caused by the industrial revolution and the influence modern housing could have had on people’s imagination. Kira Cochrane writes: “New staff found themselves 'in a completely foreign house, seeing things everywhere, jumping at every creak'. If you go to a stately home like Harewood House [in Leeds, England], you see the concealed doorways and servant's corridors. You would actually have people popping in and out without you really knowing they were there, which could be quite a freaky experience. You've got these ghostly figures who actually inhabit the house."

These elements of death, dying, and the otherworldly strongly influenced fiction in the 19th century. While the beginnings of horror fiction existed in pre-Victorian books such as The Monk by Matthew Lewis and The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe, gothic horror truly came into its own in the Victorian era. Classics such as Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, and Dracula by Bram Stoker defined tropes that still permeate the genre even today.

Although most of Katherine’s influences lie elsewhere with Chekov and Wilde, some of her writing does pick up on these horror themes set down before her. 'The Woman at the Store' is easily the best example of this. The story has a uniquely unsettling tone, and is quite unlike her later stories. It showcases a unique thread of New Zealand gothic. Take this quote for example: "There is no twilight in our New Zealand days, but a curious half-hour when everything appears grotesque—it frightens—as though the savage spirit of the country walked abroad and sneered at what it saw.”

There’s something so beautiful about that quote – an observation of New Zealand that would be picked apart by future writers, but was at the time unexplored. Even Katherine's other work that sits in a less gothic genre has a similar feel about it – for example the eerie boat journey in 'The Voyage'.

Modern media has continued this brand of Victorian gothic aesthetic. The 2010s has seen the continued use of the Victorian in fiction with movies like The Woman in Black, Guillermo Del Toro’s Crimson Peak and television shows like Penny Dreadful.

Image: Promotional poster for Crimson Peak – Guillermo Del Toro’s gothic romance film. Courtesy of Universal Pictures.

It’s incredible to think of the vast number of influences that came together to create the specific Victorian aesthetic that still fascinates people today. Maybe the reason Victorian gothic resonates so much with modern readers is the amount we have in common with our Victorian counterparts. Many Victorian concerns are ones that we still share – increasing pollution, urban migration and rapidly changing technology.

Victorian culture is often viewed as stuffy, stagnant, boring. However, imagine all the aforementioned aspects in play: moving from the country to the city, encountering strange labyrinthine buildings, electricity for the first time ever, actual human beings captured in photography on the walls, with tales of spirits and afterlives abounding. Not to mention the rise of mass media and growing relationship between the news and crime – with Jack the Ripper, Lizzie Borden and Minnie Dean all whipping up public hysteria. It would have been a strange time to live in. Living in the technology age we take change for granted given the constant and rapid change in technology around us. But for the Victorians it was new and overwhelming, and this is strongly reflected in the fiction of the time. Victorian gothic is something that continues to fascinate and influence our modern culture.

Happy Halloween, everyone!

Sources

“A Strange Beautiful Excitement: Katherine Mansfield’s Wellington 1888-1903”, Redmer Yska (2017)

“Why Were Victorians Obsessed with Death?” by Stephanie Carroll, unhingedhistorian.com

“Rituals of Sorrow: Mourning-Dress and Condolence Letters”, Pat Jalland (1996)

“Ghost stories: why the Victorians were so spookily good at them” by Kira Cochrane, The Guardian