FROM THE ASHES: THE BIRTH OF THE THORNDON SOCIETY AND THE RESIDENTIAL E ZONE

- 20 February 2019

- Eway Gateway

In the early 20th century, wooden villas sprouting from Wellington hills were constructed in the shadow of English brick grandeur. These homes were the beginnings of a vernacular; the use of abundant native woods (rimu, totara, and matai) to trim humble ‘unadorned’ villas, and the stripping back of heavy structure to withstand the city’s characteristic blusters and shakes, all amplified by their concentration in the city’s surrounding hills. And it is Thorndon, whose winding streets hold dear stories of colonial settlers, in which heritage was challenged by the promise of progress.

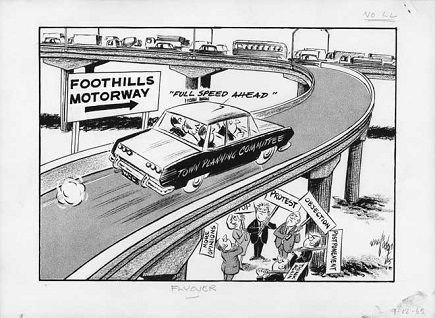

While arriving as a blessing to commuters, the 1973 Wellington motorway proposal was a road paved with destruction (literally). The motorway was proposed for access to Wellington, hoping to remedy the choke of commuters on Thorndon Quay. However, the ‘Foothills Motorway’, the council-favoured route through Thorndon Gully and Bolton St Cemetery, would cost 2,000 people their homes, and 700 dead their resting places.

Image: Cartoon by Neville Lodge depicting a protest against the Foothills Motorway being ignored by a car labelled 'Town Planning Committee', 1965. Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, B-133-312, and Te Ara.

Image: Protestors walking along a section of the Wellington urban motorway. Courtesy of Archives New Zealand - Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, AAFW 783 Box 9F, and Te Ara.

Like all good secrets, the council plan to demolish hundreds of homes soon exploded into public controversy. Activists took the streets campaigning for an alternative route to be found to avoid the destruction of the city’s heritage. This eventually culminated in campaign promises and debates in the 1965 local body elections. However, the threat of losing financial backing from the frustrated National Roads Board created sufficient pressure for the council to approve the original motorway proposal.

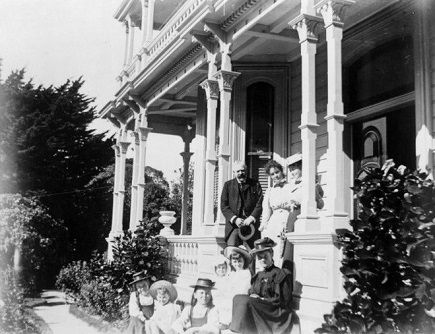

The Beauchamp family’s third home, 133 Tinakori Road, was only one of hundreds of victims of the motorway construction. Described by Katherine Mansfield as “a big white-painted square house with a slender pillared verandah and balcony running all the way around it”, Mansfield’s strong memories of the grand home inspired the setting of some of her most well-known and beloved short stories such as 'The Garden Party'. 133 Tinakori Road also marked the beginning of Mansfield’s career, as the home in which she wrote her first published story, 'His Little Friend', printed just before her 12th birthday.

Image: Katherine Mansfield with members of the Beauchamp and Ruddick families on the verandah of 75 (later 133) Tinakori Road, Wellington. Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-3320-02.

Image: Detail of 133 (previously 75) Tinakori Road, Wellington, 1968. Ministry of Works motorway design negative: 228, Reference 50006-443.

Unlike their ‘unadorned’ Tinakori Road beginnings at Katherine’s birthplace (then 11, now 25 Tinakori Road), the detailed craft of bay windows and slender verandah pillars had an air of sophistication one only hopes satisfied Mrs Beauchamp’s ‘social ambitions’. The luxury of harbour views from Katherine Mansfield’s birthplace, also suited to Mrs. Beauchamp’s aspirations, is erased from memory by the same insistent stream of cars on the motorway enabled by the destruction of their later home.

Image: The first house to be demolished for the Thorndon motorway in June 1966. Courtesy of the School of Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington.

Image: Houses affected by the motorway construction photographed in 1968. Ministry of Works motorway design negative: 230, Reference 50006-446.

Image: Thorndon during the motorway construction, 1971. Ministry of Works motorway design negative: 2191, Reference 50006-448.

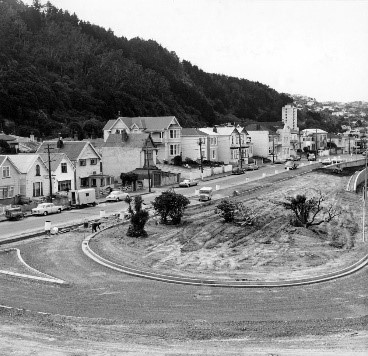

Ironically, what allows us to see details of what the home at 133 Tinakori Road was like are photos of houses that were to be demolished taken by the Ministry of Works during motorway construction from 1968-1973. Whole streets were acquired under the Public Works Act, and by 1969 the first stage of motorway construction, including the demolition of houses on Tinakori Road, was completed. Upon the opening of the motorway in 1972, a total of 3,693 human remains interred at Bolton Street Cemetery had also been dug up and moved to a common grave.

Public uproar, fueled by the belief that the council was ignoring and ‘deadening’ the city, led to the formation of the Thorndon Society. Local residents lobbied the council to restrict redevelopment of the area, seeking to preserve the suburb’s unique built heritage. Fresh from the loss of hundreds of homes, in 1976 Thorndon became New Zealand’s first built heritage conservation area after it was named a Residential E Zone. The official respect for the combined heritage of Thorndon’s buildings, street character and landscape halted plans for new high rises in the area and inspired similar zoning to preserve the heritage of neighbourhoods throughout New Zealand. The government also helped to preserve the area when it introduced housing improvement loans in the 1970s. This brought a new wave of young couples to Thorndon, who bought and refurbished old homes.

A history of community lobbying to protect built heritage in Wellington, while not saving 133 Tinakori Road, paved the way for Katherine Mansfield’s birthplace at 25 Tinakori Road to be recognised as a place of national significance.

Today, Katherine Mansfield House & Garden continues to be open to the public due to the community spirit of care for our local heritage.

References:

'M.O.W. Welington Urban Motorway Construction', Wellington City Recollect.

'Thorndon historic district leads the way in urban design', Victoria University of Wellington School of Architecture.

Schrader, Ben. 'City planning: From motorways to the Resource Management Act' (pp.4-5), Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.