IN MEMORY OF LESLIE HERON BEAUCHAMP

- 23 April 2024

- Cherie Jacobson

Each year on 25 April, Anzac Day commemorates all New Zealanders killed in war and honours returned service personnel. At Katherine Mansfield House & Garden, we particularly remember Katherine Mansfield’s younger brother, Leslie Heron Beauchamp, who died in the First World War, aged 21.

Image: Portrait of Leslie Heron Beauchamp taken by an unknown photographer, c1915. From the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-6826-1-48.

This year is the 130th anniversary of Leslie’s birth on 21 February 1894. By this time, Katherine’s parents Harold and Annie Beauchamp had left the house at 25 Tinakori Road that is now Katherine Mansfield House & Garden, and were living in Karori with their four daughters (a fifth daughter had died aged just three months in 1891). In his memoir, Reminiscences and Recollections, Harold Beauchamp wrote:

“You can imagine what happiness the arrival of the boy brought as the last of the family…His coming was a great joy to us and he was truly a blessing in every respect. Leslie went to Miss Swainson’s preparatory school in Fitzherbert Terrace; was for a while at Wellington College, and, in 1908, went to the Waitaki Boys’ High School…and had the happiest time of his life there. Besides receiving a sound classical education he was a good all-round athlete and sportsman, playing cricket, rugby, and tennis. Shortly after leaving school (at the end of 1910) he went Home [to England, known by many New Zealanders of British descent as ‘Home’ at that time even if they had never lived there] with my wife and his sisters to see the coronation of King George V.

Like other members of the family, Leslie was endowed with considerable literary ability, and I think he would have liked to follow a literary career; but in deference to my wishes he adopted business and came into the firm to learn.

On the declaration of war he wanted to join the Expeditionary Force to Samoa, in which many of his friends had volunteered, but his mother was seriously ill and I persuaded him not to go. He went about for a week or two looking the picture of misery, and then came to me and said, “Dad, I must go to the war. All my schoolmates are volunteering.”

I said, “What does your mother think about?”

Leslie said, “I have discussed it with her, and she is just as keen for me to join up as I am myself.”

Accordingly, I arranged for him to go to London in one of the Tyser steamers with his friends Higginson and Tiddy Johnston. Alas, all of them were killed. Within a fortnight of reaching London Leslie obtained a commission in the 8th battalion of the South Lancashire Regiment, and after six months’ training he crossed over to France (September, 1915). He had qualified as a bombing officer, one of the most dangerous duties a man can take on, and by the premature explosion of a bomb in his hand at Ploegsteert wood he was killed (7th October, 1915). This was a great blow to us all, the sudden ending of a young life in which all our hopes were centred. The void thus made has never been filled, as you can imagine. Writing to my wife after the sad event, the colonel of his regiment said, “He was a most promising soldier and I can only say that he was the idol of his regiment.” A fine tribute, wasn’t it? Leslie was buried on the field, a little north of the Armentières and just across the French border.” [1]

While onboard the ship to England, Leslie kept a diary, a copy of which is now held in the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library. The Library also has letters Leslie sent to his family and friends during his training, then once he had arrived in the war zone in France. During training Leslie was able to visit his sister Katherine and her partner John Middleton Murry at their home in London. In a letter to his parents on 25 August 1915 he wrote, “I had a most comfortable roost at Kathleen’s dear little house in Acacia Road, St John’s Wood - Jack Murry is a very kind quiet soul and he and K are perfectly sweet to each other – in fact I was awfully glad to see how smoothly things were running.” During their time together, Katherine and Leslie reminisced about their childhoods in Wellington, playing the ‘Do you remember?’ game in which they tried to recall as much detail as possible about places, people, and events.

Image: Katherine Mansfield (centre) as a teenager with her younger sister Jeanne (left) and brother Leslie (right) taken by an unknown photographer in 1907. From the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-011986-F.

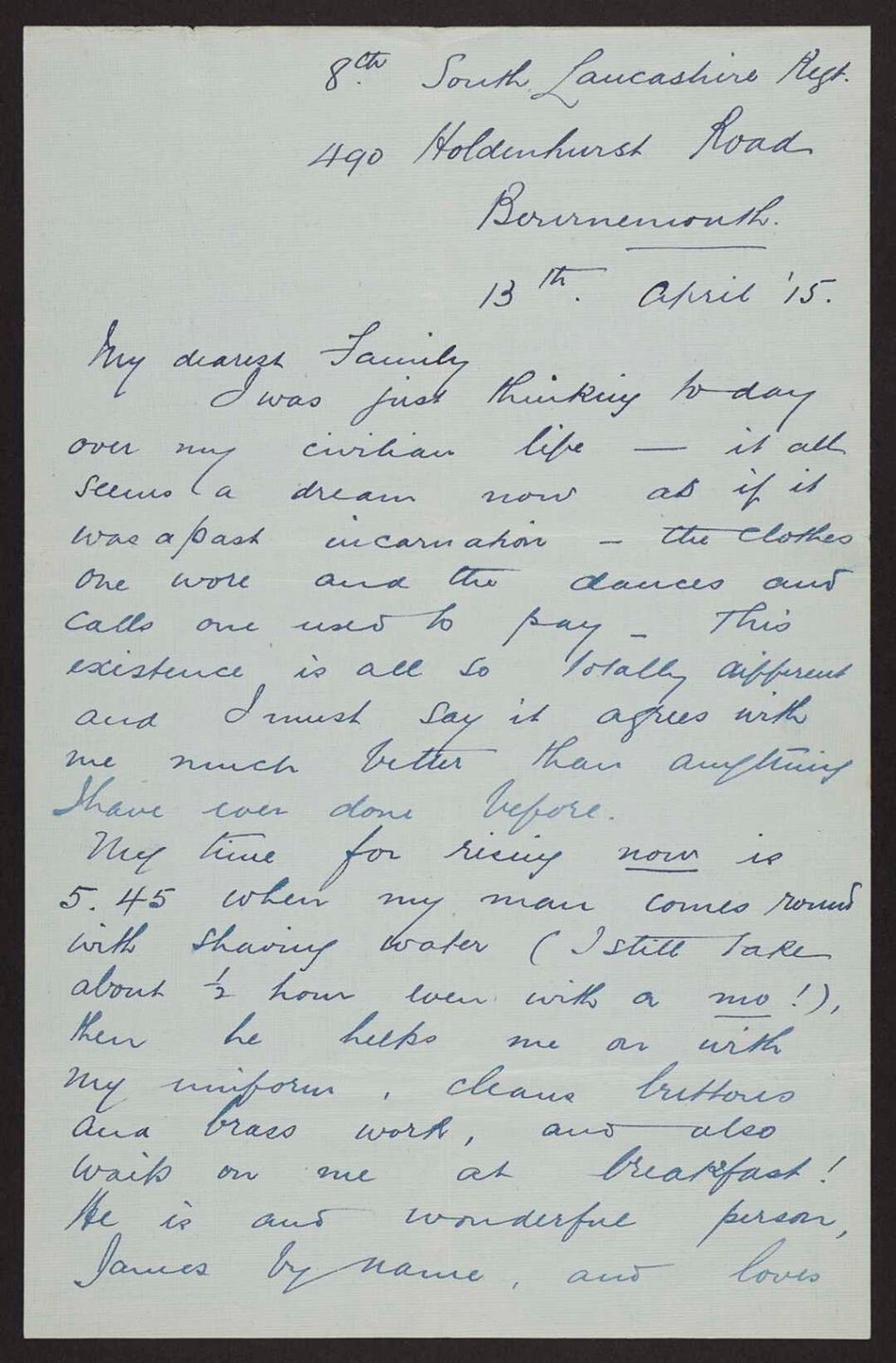

In his writing Leslie comes across as a cheerful, sociable young man enjoying his new life as a soldier in training and making the most of time off to meet up with friends for meals and even attend a few theatre shows. A letter from 13 April begins, “My dear family, I was just thinking today over my civilian life – it all seems a dream now, as if it was a past incarnation – the clothes one wore and the dances and calls one used to pay – this existence is all so totally different and I must say it agrees with me much better than anything I have done before.”

Image: Letter dated 13 April 1915 from Leslie Beauchamp to his family. From the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, MS-Papers-2063-03-1.

After months of training, he became eager to be part of the action, writing on 21 September, “We are just off to France after months of weary waiting. Swell, now is the time for us to show what we are really made of and I pray God that I will prove myself worthy of your love and trust in me.” He mentions in subsequent letters that he is “fit as a fiddle and full of beans.” Although he may have been exaggerating his enthusiasm for the benefit of his family, especially as he was so determined to enlist, it is hard not to believe he really was in a positive frame of mind. Given Harold Beauchamp acknowledged his son may have had dreams other than a career in business, perhaps Leslie was just happy to have escaped his fate behind a desk in Wellington and was making the most of the ‘adventure’ he had chosen to pursue through war service.

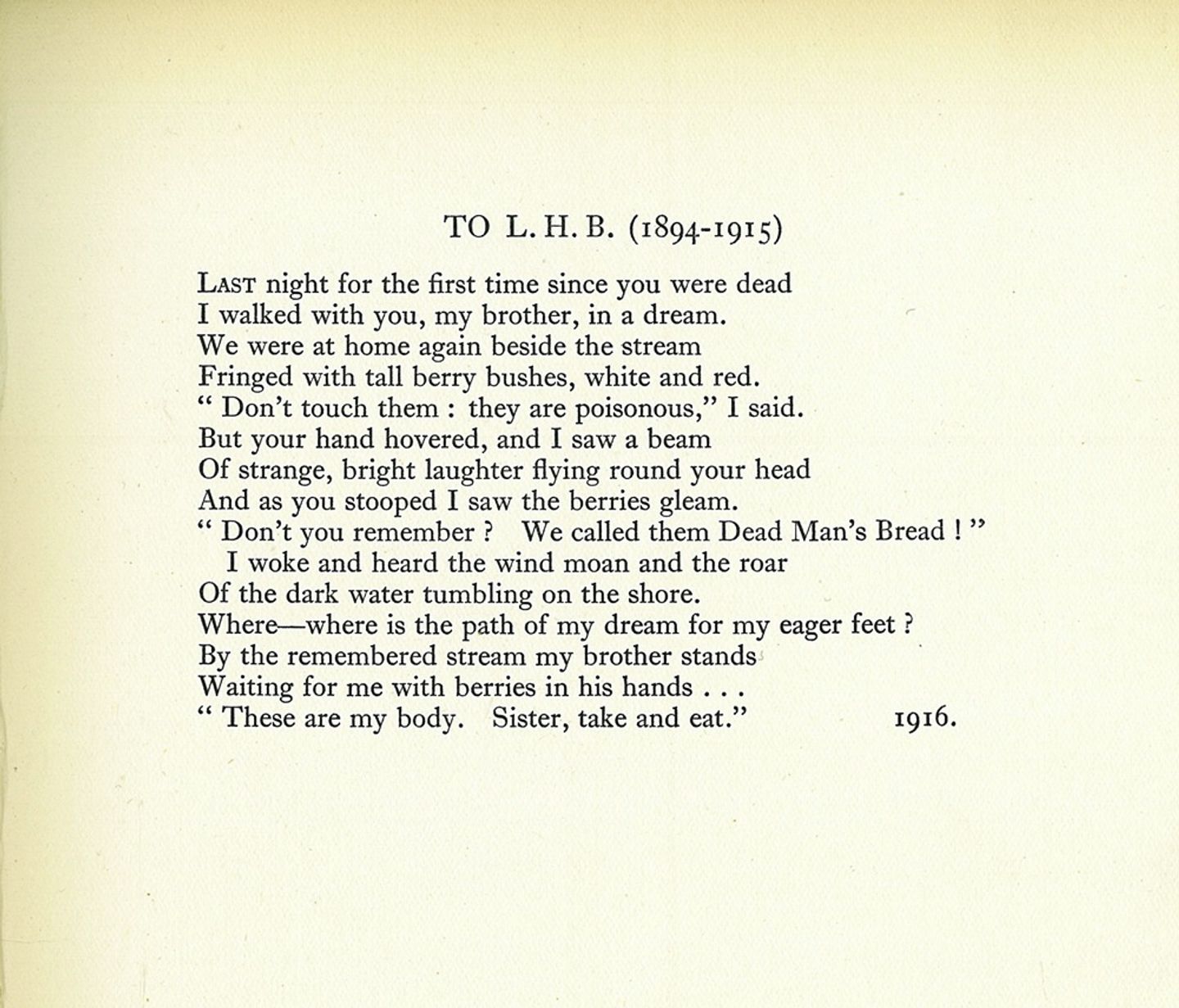

After Leslie’s death, Katherine felt driven to write about her childhood, “I feel I have a duty to perform to the lovely time when we were both alive. I want to write about it and he wanted me to.” [2] Her memorial to Leslie was her stories inspired by their family life, including ‘Prelude’, ‘At the Bay’ and ‘The Garden Party.’ Katherine felt she and Leslie shared a special connection, which may explain why the characters they inspired in the ‘The Garden Party’ have female and male versions of the same name – Laura and Laurie. Harold mentions their connection in his memoir, “My wife was sadly shaken by the loss of her youngest child and her only boy. If possible Kathleen felt it even more deeply. Leslie and she had been inseparable whenever they were living together.” [3] One of Katherine’s last completed stories also pays tribute to her brother; in ‘The Fly’ a businessman grieves for his only son, killed six years earlier in the war.

Video: You can watch local actor Peter Hambleton reading ‘The Fly’ above. A version of this reading with an introduction to the life of Katherine Mansfield and the story can be found here.

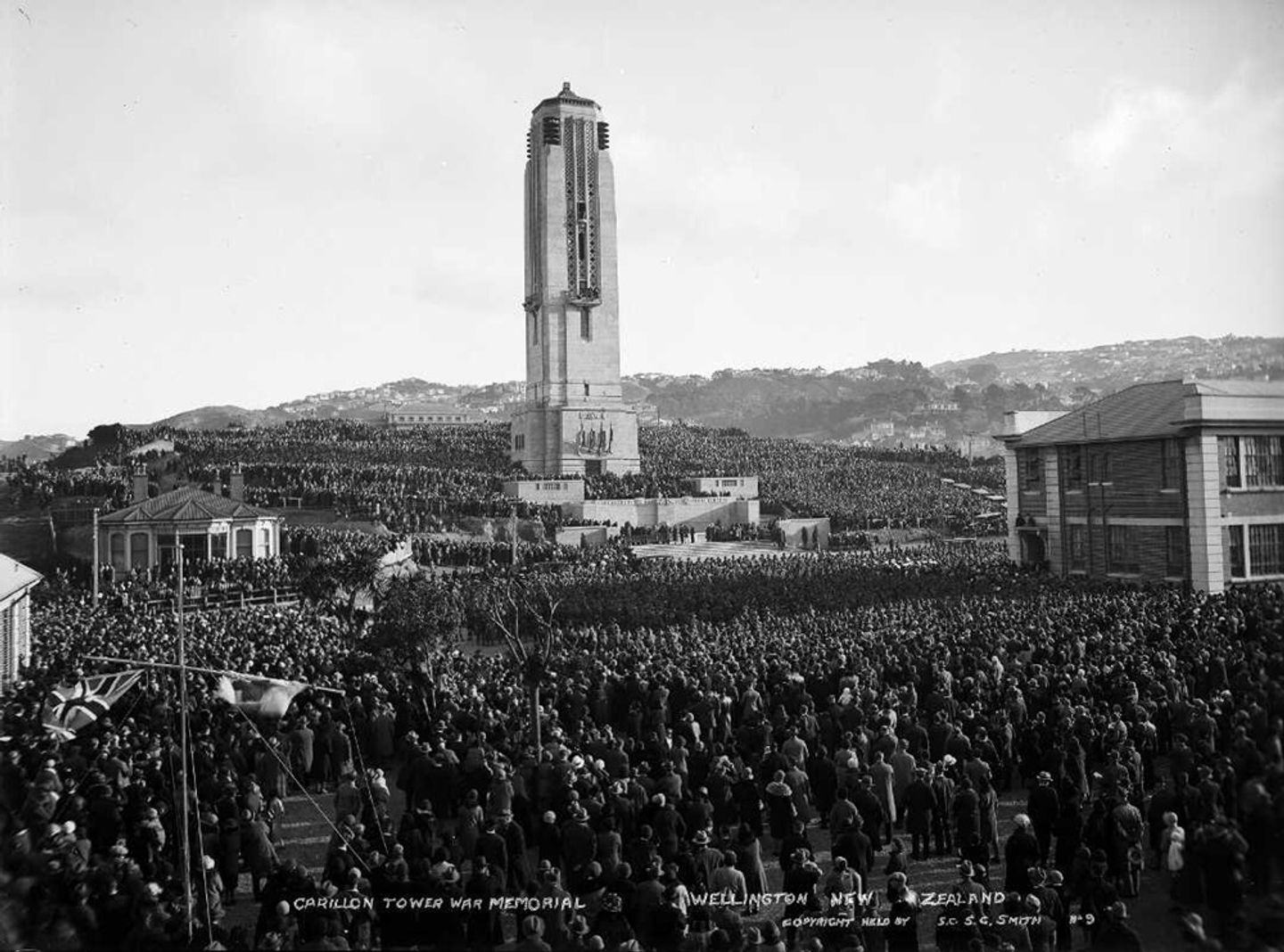

Harold Beauchamp also created his own public memorial to Leslie by playing a key role in the creation of the National War Memorial Carillon, now part of the Pukeahu National War Memorial Park in Wellington. In 1925, Harold was elected the first President of the Wellington Carillon Society, the group that began the push for a memorial carillon (bell tower). [4] The following year he purchased a large bell in memory of Leslie, an act of great faith in the project given the Society had yet to confirm the building of a tower to house the bells, let alone the location for the tower. [5] There was great enthusiasm from the community for a carillon though, and after the opportunity to purchase bells was presented, the Society was quickly oversubscribed with applicants.

The bell for Leslie is called the Flanders Fields Bell, you can see a photo of it here. It weighs 1,269kg and is inscribed:

“Flanders Fields”

In Ever Loving Remembrance of

Leslie Heron,

Only Son of Harold and Annie Burnell

Beauchamp

Work finally began on building the Carillon in 1931 and it was dedicated on Anzac Day 1932. Reporting on the first recital of the Carillon, the Evening Post said, “last night the air was filled with music for one entrancing hour. Thousands of people stood as if spellbound … listening to the music flowing out from the louvres in the tall tower and flooding the city with melody and harmony of indescribable beauty.” [6]

Image: A photography by Sydney Charles Smith of the crowd of people who attended the dedication of the carillon on 25 April 1932. From the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/1-020293-G.

Leslie Beauchamp’s story was included in the series Great War Stories (you can watch the four-minute video here) and as part of the teaching resource Walking with an Anzac. Katherine’s moving poem dedicated to her brother, ‘To L.H.B.’, has been recorded as a song by Julia Deans, you can watch her performing it here.

Image: A published version of 'To L.H.B.' to Katherine Mansfield.

References:

[1] Beauchamp, Harold. Reminiscences and Recollections. New Plymouth: Thomas Avery & Sons Ltd, 1937. P.83, 92-93

[2] Mansfield, Katherine. Journal entry 20 October 1915.

[3] Beauchamp, Harold. Reminiscences and Recollections, p.94.

[4] ‘Carillon rejected’, Evening Post, 11 December 1925, p.9.

[5] ‘Grand Carillon’, Evening Post, 11 June 1926, p.8.

[6] ‘The new music’, Evening Post, 26 April 1932, p. 10.