KATHERINE AND PHOTOGRAPHY

- 21 July 2022

- Web Master

During her Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington Museum and Heritage Studies placement at Katherine Mansfield House & Garden in June 2022, Louise Mitchell took a particular interest in two boxes of collection items relating to photography. She wrote this wonderful blog post about some of the objects and the development of photography during Katherine Mansfield's lifetime. Thank you Louise!

Over the last month of completing my placement at Katherine Mansfield House & Garden, I have primarily been helping to update catalogue records for boxes of items from the House’s collection. Of the 13 boxes I helped get up to date, it was the objects in Photography Boxes 1 and 2 that perhaps captured my imagination the most and that I ultimately chose to research in more depth. Along with other objects, these boxes contained multiple copies of photos of Katherine Mansfield. Using the knowledge about Katherine that I have picked up throughout my placement, it has been fascinating to connect Katherine and photography: two topics which at first glance may appear completely disconnected. However, during Katherine’s life (1888-1923), photography was undergoing a huge transformation and Katherine’s own experiences as a photographic subject help to demonstrate this. In fact, this can perhaps be best illustrated by the fact that the first film roll was created only the year after her birth, and that the first 35mm camera, an innovation which made photography increasingly portable, was created only two years after her death.

.jpg?202207202310)

Image: Children from the Beauchamp family and others seated in the garden of number 75 Tinakori Road (a property that was demolished during the construction of the Wellington Urban Motorway). Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp (who would later choose to use the name Katherine Mansfield) is sitting second from left, next to her youngest sister Jeanne. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-3320-01.

Despite the newness of photography during her lifetime, Katherine was in front of a camera surprisingly often. There are plenty of photos of Katherine and her siblings as children. Some are formal but others (such as the one above) are less so, which suggests that the family may have either had their own or access to a privately owned camera. As an adult, there is ample evidence that Katherine's social circle was involved with photography. Her longtime friend and frequent companion, Ida Baker, is credited for multiple photos of Katherine, and another photo of her at Garsington Manor was taken by Lady Ottoline Morrell, Katherine’s host. Such photos show us a curated but more casual glimpse into Katherine’s life: in her London flat, on her travels, reading in the garden.

.jpg?202207202328)

Image: Katherine Mansfield photographed by Ida Baker at Katherine's home in West Kensington, London, 1913. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/4-059876-F.

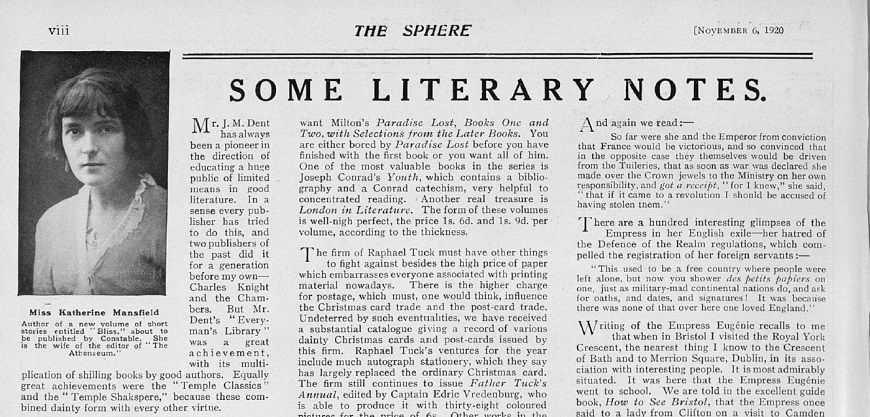

Katherine also engaged with professional photography. One example is a shot taken at Adelphi Studios in London, which she later expressed an intense dislike for upon its publication in The Sphere, an illustrated newspaper. Upon seeing the photo published, she sent an angry telegram to her husband John Middleton Murry: “INTREAT YOU! LET NOONE HAVE HIDEOUS OLD PHOTOGRAPH PUBLISHED IN SPHERE IMPORTANT BURN IT” as well as, on the same day, a letter of explanation: “I feel quite ill with outraged vanity. . . It’s not me. It’s a HORROR.”[1] Just over a week earlier, Katherine had also written a letter to John about her fascination with photography studios and even the possibility of putting one in a future story.[2]

Image: A page from the illustrated newspaper The Sphere, showing a photograph of herself that Katherine Mansfield called "hideous" and a "horror."

Katherine’s experiences with photography reflect a wider societal pattern at the time, when photography was still perceived as a novelty but was an increasingly regular part of life. Below, I outline three types of items within the collection of Katherine Mansfield House & Garden, which I believe particularly demonstrate the development of photography during Katherine's lifetime.

Image above: An ambrotype portrait of an unidentified child held in the collection of Katherine Mansfield House & Garden. Gift of Lorna O'Hagan.

Ambrotype

One of the most interesting photographs I found in the collection is an ambrotype of a young child, tightly bound in a golden frame. Ambrotypes were a cheaper and faster way to take photos than their predecessor, the daguerreotype, which had been the first commercially viable photographic process.[3]

When taking an ambrotype, the image is underexposed onto a glass plate, making it appear white.[4] This means that when a black backing is placed behind the glass, shadow is provided to contrast with the captured lightness of the photo. This makes the two plates combine into seemingly one image: a black and white photo.

Due to their affordability, ambrotypes were an embraced method of photography, but did not rise to the success of their predecessor and the creation of film after Katherine Mansfield was born shows how the field was quick to move on. The first New Zealand ambrotype studio, The Wellington Ambrotype Portrait Gallery, opened on Lambton Quay in 1857 but closed the following year.[5]

By the time Katherine was born in 1888, ambrotypes would have been an increasingly unpopular method of photography. While still available in a limited capacity, they were increasingly referred to in terms of the past in newspaper articles of the day.

Yet despite what may be seen as limited success, the rise of ambrotypes left behind a legacy of many small portraits, made up of two glass plates bound in frames, and many have been kept as treasured possessions. Due to the layering effect of the two glass plates, an almost holographic illusion for the viewer is created. This is especially clear in Katherine Mansfield House & Garden's ambrotype of the young child, as cracking in the dark back layer reveals the inner layers of the ambrotype. The processes of creation are therefore quite visible within the photo, yet the image itself is still visible. Because of this, I believe this is a particularly valuable piece for contemporary audiences wanting to learn about the history and creation of photography.

Image: A stereoscope in the collection of Katherine Mansfield House & Garden. Donor unknown. You can see an image of a similar one being used here.

Stereoscope

Another exciting piece in the collection is a handheld stereoscope. A stereoscope uses two images of one subject, taken from slightly different angles, to create a three-dimensional perspective for the viewer, who looks at the images through lenses typically built into the stereoscope.[6] This effect was discovered in 1838 by Charles Wheatstone and made portable around a decade later.[7]

The stereoscope in Katherine Mansfield House & Garden's collection follows the conventions of the Victorian era. It is a wooden device with a well-sculpted handle, which assists the viewer in holding the lenses to their eyes, from which the viewer can best see the effect. This stereoscope is a relatively ornate example of its kind, with many more rudimentary models in existence. Other styles include boxes, pocket fold-out tins, and stereoscopes on permanent stands. The wide range of stereoscope styles is a reflection of their global popularity, which began in the 1850s and continued until their decline in the 1910s.[8] In New Zealand, a similar if not slightly delayed, history took place, which can be traced through newspaper articles and advertisements of the time.

Newspapers show that the stereoscope likely first arrived in New Zealand in 1854, when a Mr Moore brought one to the Wellington Mechanics’ Institute’s annual 1854 Conversazione.[9] It was accompanied by stereographs (the photos used in the stereoscope) of the 1851 Great Exhibition in England and received considerable attention throughout the evening.[10]

Stereoscopes became increasingly commonplace in the following decades. They began being advertised for sale from the 1860s and ranges of stereographs were also increasingly made available, such as of European tourist spots or New Zealand nature. New Zealand Graphic magazine offered a complimentary stereoscope and stereographs upon purchase of a magazine subscription, making them even more accessible to the public.[11] Five of the cards associated with this promotion reside in Katherine Mansfield House & Garden's collection today. The majority of them depict black and white scenes of Days Bay, where the Beauchamp family enjoyed holidays. The link of these cards to the New Zealand Graphic is also appropriate as the New Zealand Graphic was one of the first publications to publish Katherine Mansfield’s writing, back when she was 11, and that she corresponded with one year later.[12]

The House also has a set of 56 stereographs, which depict international tourist scenes. The ability to offer viewers 3D scenes of places they had never visited was a huge part of the appeal of the stereoscope and these views would likely have been popular when Katherine was a child. For many young New Zealanders at the time, such views of England and Europe may have been the first time they had seen these places - places their parents or grandparents were born; for those older relatives, the stereoscope offered a nostalgic view of their homeland.

Although the demand for stereoscopes began dying away after the turn of the century, their appeal and legacy has never completely disappeared. The 3D effect was replicated for a new generation in the 1960s with the View-Master and more recently can be seen in the appeal of virtual reality headsets.[13] Just as New Zealanders in the 1850s enjoyed viewing the Great Exhibition through a stereoscope, contemporary New Zealanders are now increasingly able to experience overseas exhibitions and museums through virtual reality.

Image: Album of postcards in the collection of Katherine Mansfield House & Garden. Donor unknown.

Cards

Despite the decline in popularity of the stereoscope, the appeal of collecting novelty and tourist photos did not diminish and still exists today. Another iteration in Katherine Mansfield's time was the rise of the postcard. Postcards became popular at a time when the average traveler was unlikely to have their own camera, offering tourists a cheap and portable way to show off their travels. Katherine Mansfield House & Garden has a beautiful postcard album from this era, where purchased postcards from tourist spots all over England were dutifully stuck into the album’s slots. Around the same time these postcards were being collected, Katherine herself sent a postcard of her school, Queen’s College in London, to her cousin Lulu back home in Wellington.[14]

A similar memento of this nature in the collection is cigarette cards. Cigarettes and smoking have a long association with reading and contemplation, particularly in England.[15] By the nineteenth century, this had developed into the cigarette card, which presented smokers with a small token of information to read.[16] These cards classified information into series on different topics, which offered loyal consumers an even spread of knowledge on topics such as nature, trains, or celebrities.[17]

Photography was embraced as an addition to cigarette cards. The cigarette card in Katherine Mansfield House & Garden's collection depicts a black and white photo of a tall post. Information on the back of the card explains that this is a resting post, where workers carrying objects could rest their load. The card is part of a collection called 'Links with the Past' and was created by Sarony & Co. There is even an offer at the bottom of the card, telling consumers that if they collect all 25 cards in the set, they can send them away to be bound for free - a further incentive to buy more cigarettes and collect all the cards! While many cards were likely collected, with the card in Katherine Mansfield House & Garden's collection as an example of this, the low quality and minimal information incorporated into the design suggest many cards would have been quickly discarded.

The ephemeral aspect of the cigarette card is what makes it so noteworthy in the history of photography, as it demonstrates how photography had become so accessible that it could now be discarded after a glance. It is interesting to compare this with the ambrotype in Katherine Mansfield House & Garden's collection, where a photo of a similar size and quality would have been a rare and likely prized possession. In just over the length of Katherine Mansfield’s life, we can therefore trace how photography went from a luxury to an accessible aspect of everyday life.

References

[1] Telegram from Katherine Mansfield to John Middleton Murry, 14 November 1920 (spelling of 'intreat' as per original) and letter from Katherine Mansfield to John Middleton Murry, 14 November 1920.

[2] “Oh, by the way, I had my photo taken yesterday – for a surprise for you. I’ll only get des epreuves on Monday tho. I should think it ought to be extraordinary. The photographer took off my head & then balanced it on my shoulders again at all kinds of angles as tho it were what Violet calls an art pot. “Ne bougez PAS en souriant leggerreMENT – Bouche CLOSE.” A kind of drill. Those funny studios fascinate me – I must put a story in one one day. They are the most temporary shelters on earth. Why is there always a dead bicycle behind a velvet curtain? Why does one always sit on a faded piano stool? And then, the plaster pillar, the basket of paper flowers, the storm background – and the smell. I love such endroits.” From a letter Katherine Mansfield sent to John Middleton Murry, 5 November 1920.

[3] Jill Haley, 'The Day Photography Was Born,' Canterbury Museum (Blog), 7 January 2019.

[4] Christina Finlayson, 'Through the Looking Glass – Stabilization of an Ambrotype,' National Portrait Gallery (Blog), 18 August 2017.

[5] 'Page 4 Advertisements Column 1,' Wellington Independent, 28 July 1858, p.4.

[6] [7] [8] Clive Thompson, 'Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality,' Smithsonian Magazine (Blog), October 2017.

[9] New Zealand Spectator and Cook’s Strait Guardian, 9 September 1854, p.3.

[10] 'Mechanic’s Institute,' Wellington Independent, 16 September 1854, p.3.

[11] 'Free Stereographs and Views,' Nelson Evening Mail, 11 April 1907, p.2.

[12] Kathleen Beauchamp, 'His Little Friend,' New Zealand Graphic, 13 October 1900, p.710; and 'Children’s Page,' New Zealand Graphic, 8 June 1901, p.1098.

[13] Clive Thompson, 'Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality,' Smithsonian Magazine (Blog), October 2017.

[14] Postcard to Lulu Dyer in the collection of Katherine Mansfield House & Garden.

[15] Susan Zieger, The Mediated Mind: Affect, Ephemera, and Consumerism in the Nineteenth Century, Fordham University Press, New York: 2018, p.55.

[16] [17] Hermann Mückler, 2019, 'The representation of the New Guinea tree house in the historical popular medium of the trade card,' Journal of New Zealand & Pacific Studies 7(1): p.21.