MANSFIELD IN THE TIME OF COVID-19

- 20 April 2020

- Nicola Saker

Katherine Mansfield rarely fails to be relevant. Even now, in this time of COVID-19, Mansfield’s experience offers insight.

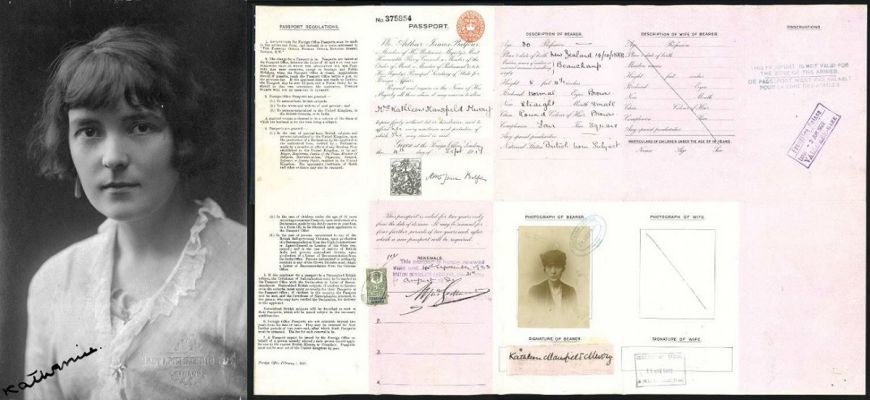

Image: (left) A studio portrait of Mansfied in 1914 (Adelphi Studios Pickthall); (right) A diminished Mansfield in her British passport (issued in the name of Mrs Kathleen Mansfield Murry, 4 September 1919). Entries in the passport show evidence of her last years of travel through Europe, searching for a cure for her tuberculosis. Both images courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/4-017274-F and MS-Papers-11326-070.

Mansfield was no stranger to public health emergencies. When she was born in Wellington on 14 October 1888, raw sewage was flowing into her hometown’s harbour. Outbreaks of typhoid, cholera and other infectious diseases were frequent: between 1885 and 1891, almost 550 Wellingtonians died from them.[1] Amongst them were Mansfield’s baby sister, Gwendoline, and her uncle, Charles. One of the most significant events of Mansfield’s childhood, the move from 25 Tinakori Road to Chesney Wold in Karori, is thought to have been prompted by the threat of infectious diseases in central Wellington.[2]

Another, later, fatal health emergency was her exposure to tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (also known as TB), is a bacterial infection that most commonly affects the lungs, but can also affect the lymph nodes, bones, joints and kidneys. The bacteria had been around for a very long time and constituted a never-ending pandemic. For 17,000 years it ebbed and flowed all over the world, but the Industrial Revolution in Britain with its urbanisation, crowded housing and poor sanitary conditions embedded tuberculosis into British life in the 19th century.

In 1908, Mansfield returned to London, regarded as the epicentre of Western cultural life. It was also the epicentre of tuberculosis. By 1917, when she was first diagnosed as having a “spot” on her lung and advised to go abroad, the disease was felling 1,000 British citizens a week. Antibiotics developed in the 1940s and 1950s provided an effective treatment, but this hasn't resulted in TB's eradication. Rather, it has gone underground and often remains undetected amongst the homeless and those suffering from substance addictions. Approximately 5,000 UK citizens are diagnosed with TB every year and nearly 40% are Londoners.[3]

Image: Plus ça change – St Thomas’ Hospital (London) was, and still is, the place to be. Tuberculosis patients from St Thomas’ Hospital rest in their beds by the River Thames in May 1936, opposite the Houses of Parliament. Courtesy of Fox Photos/Getty Images.

TB was known as the illness of storytellers and Mansfield was acutely aware of its impressive, but deadly, literary lineage: Keats, all three Brontë sisters (plus their brother, Branwell), Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov. That both Keats and Chekhov were medically trained adds another layer of poignancy to their illness. They knew, intimately, exactly what the disease was doing to them.

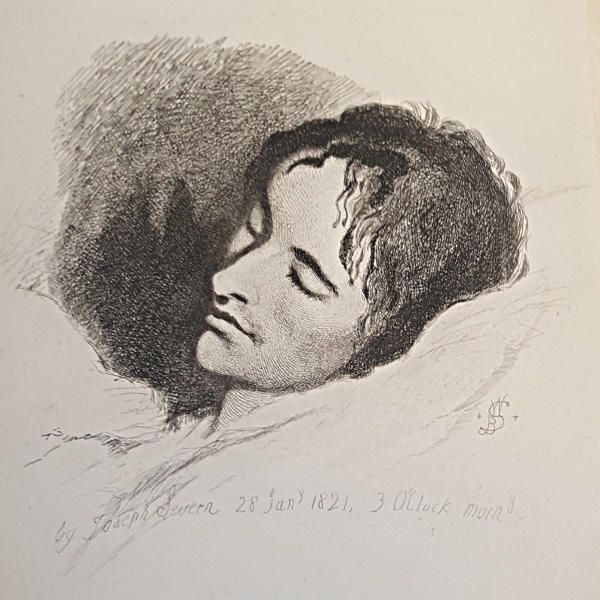

Image: John Keats on his deathbed, 28 January 1821, drawn by his friend Joseph Severn. Courtesy of Project Gutenberg.

The romantic association of writers and the illness truly took hold with Keats in a similar way that death by drug abuse has with contemporary rock culture. The anthem ‘Live fast, die young, have a good-looking corpse’ has echoes of Keats’ portrayal of the effects of TB as "youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies", along with the image of the patient being "half in love with easeful death".[4] His friend, Joseph Severn, drew him on his deathbed in Rome and fixed forever the image of the tragic consumptive and the desire to "fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget".[5]

Keats had travelled to Rome for a change of climate and Mansfield’s last years were spent moving from place to place in Europe, seeking a climate that might help her condition as well as various treatments on offer. But the travel meant coming up hard against the stigma of the disease. In Italy, TB was a notifiable disease and viewed with terror, so, in San Remo she was asked to leave a hotel by its manager because of the risk to the health of his other guests. She was subsequently sent a bill for her room’s fumigation.

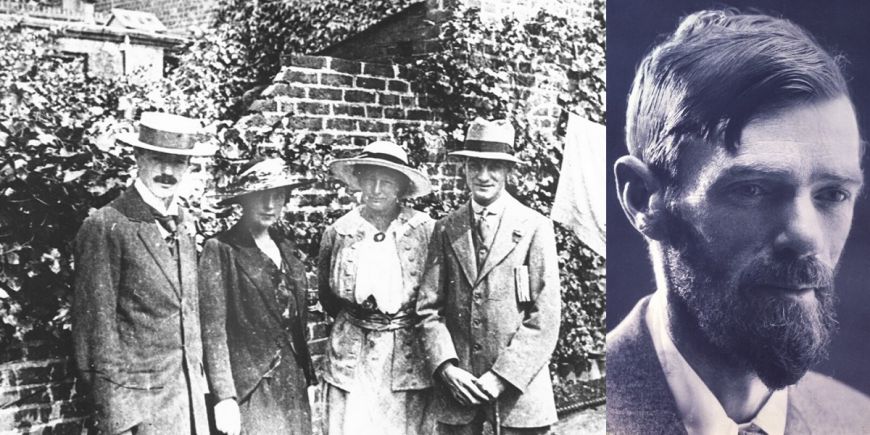

Such stigma meant that victims of TB often simply denied having the disease. D.H. Lawrence, who quite likely contracted the illness as a child in Nottingham, never admitted to it and may possibly have infected Mansfield. The shame of being infected continues today, with one University College London specialist, Dr Al Story, explaining he has patients who say they would rather have AIDS than TB.[6]

Images: TB or not TB? The photograph on the left shows D.H. Lawrence (far left) with Mansfield, Frieda Lawrence and John Middleton Murry on the Lawrences' wedding day in 1914. The photograph on the right, by Ernesto Guardia, shows Lawrence in 1929, the year before his death. Lawrence, weighing 44kgs and with collapsed lungs at the end of his life, maintained he was 'bronchial'. Images courtesy of The University of Nottingham and the National Portrait Gallery (UK).

Mansfield and Lawrence shared the illness and also one of its characteristics: ‘phthisical’ rages in which both said or wrote truly appalling things. From him to her: "You revolt me stewing in your consumption."[7] From her to husband John Middleton Murry, about her companion, Ida Baker: "Christ! to hate like I do … I’m simply a blind force of hatred … her great fat arms, her tiny blind breasts, her baby mouth, the underlip always wet and a crumb or two or a chocolate stain at the corners."[8] Earlier, in 1917, when she was first diagnosed, a doctor ordered bed rest and she wrote: "I am still feeling prestissimo. In fact, I can’t sleep for a nut. I lie in a kind of furious bliss."[9]

By the time of the ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic in 1918, Mansfield’s tuberculosis was well-established and she would have been particularly vulnerable. At that time, she and Murry were living at 2 Portland Villas, East Heath Road, Hampstead. It was a healthy choice, given Hampstead’s higher ground and less polluted atmosphere, along with its less dense housing. Her family didn’t escape it, however, and in Wellington her Uncle Val was a victim, as was her great-aunt Louie, the mother of her writer cousin, Elizabeth von Arnim.

Mansfield’s ‘bubble’ was frequently just herself, but often included her friend Ida Baker, and occasionally Murry, sometimes with, and sometimes without, Baker. It is possible, in the current climate, to imagine quite how claustrophobic such arrangements would have been.

From February to May 1922, Mansfield spent roughly three months in isolation in a hotel room in Paris, as she underwent a series of X-ray treatments to try to cure her TB. The treatment was very painful, and she was often confined to bed. Initially, she was alone, but Murry soon joined her and in letters she described a routine of working, playing chess, reading, and drinking tea. She commented to her friend Dorothy Brett in a letter, “It’s rather like waiting to have an infant – newborn health.”[10] It was during this time she wrote ‘The Fly’.

Writers often mine their own lives for material and Mansfield was no different, using her illness as a source. In the poem ‘Malade’ the speaker lies in her hotel room coughing:

The man in the room next to mine

Has got the same complaint as I

When I wake in the night I hear him turning

Then he coughs

And I cough ….

They are, Mansfield says, "like two roosters calling to each other at false dawn". Mansfield scholar Professor Jane Stafford has written: "I think this is my favourite [Mansfield poem] because it manages to convey the awfulness of being ill with a rueful humour – and a sense of how you cast this terminal experience into literature – even if it’s just a matter of noticing syncopated coughing."[11]

References

[1] Hunt, Tom. 'Historian probes deadly Mansfield undertones', The Dominion Post, 17 Dec 2014.

[2] Yska, Redmer. A Strange Beautiful Excitement: Katherine Mansfield's Wellington 1888-1903. Otago University Press, 2017. pp.55-67.

[3] Wilson, Frances. 'How London became the tuberculosis capital of Europe', The Guardian, 26 Nov 2018.

[4] & [5] Keats, John. 'Ode to a Nightingale', 1819.

[6] See [3].

[7] Mansfield, Katherine. Journal, 1 Feb 1920.

[8] Mansfield. Letter to John Middleton Murry, 20 Nov 1919.

[9] Alpers, Antony. The Life of Katherine Mansfield. Viking, 1980. p. 264.

[10] Mansfield. Letter to Dorothy Brett, 14 Feb 1922.

[11] Stafford, Jane. 'Mansfield Unplugged: The Poetry of KM', KMHG blog, 6 Apr 2020.