MANSFIELD UNPLUGGED: THE POETRY OF KM

- 6 April 2020

- Web Master

Jane Stafford, Professor in English Literature at Victoria University of Wellington and self-described Mansfield 'fangirl', delivered this short talk on Mansfield's poetry at the launch of Mansfield, a new album of Mansfield poems interpreted by leading New Zealand musicians.

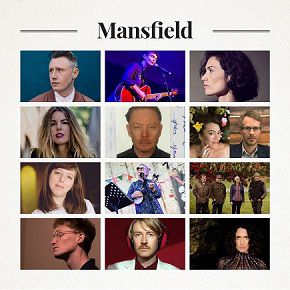

Images from the Mansfield album launch (from left): Prof Jane Stafford speaks; the album cover; Charlotte Yates and band perform.

Katherine Mansfield did not see herself as a poet. She was certainly a very self-conscious, professional, focused and strategic writer but poetry was, for her, not a central form. Early on in her career, she did gather together two collections of poetry. But they were not successful. An abrupt response to one poem’s submission to an Australian journal reads: ‘KB (NZ) Sorry unsuitable’.

The poems Mansfield did publish, here and when she arrived in London, often appeared under a pseudonym – ‘Boris Petrovsky’ was a favourite pen name, reflecting her enthusiasm for things Russian, ‘Lily Heron’ another, ‘Julian Mark’ yet another. In part this was the time-honoured strategy of all small literary journals who wish to imply they have a large and energetic staff of dozens of writers in bright shiny offices, whereas they are in fact produced on the brink of bankruptcy, by the editor and their best friend on the kitchen table.

But it’s also an indication of Mansfield’s studied aversion to authenticity, to being visible on the page. Odd for a writer but bear with me. Writing – indeed, life in general – is for Mansfield about performance, artifice, the wearing of a mask – she wrote, ‘Don’t lower your mask until you have another mask prepared beneath – as terrible as you like – but a mask’. As for being authentic: ‘True to oneself!’ she asked, ‘Which self? Which of my many - well, really, that’s what it looks like coming to - hundreds of selves?’

So, as a writer she appears under a raft of disguises – born Kathleen Beauchamp, she becomes Katherine Mansfield, Kass, Kathe, Katerina, Boris, Julian or Lily. Reality is held at a distance. At one point she wrote in her notebooks, ‘Whatever actually occurs is spoiled for art.’ And her stories work with indirection and disguise, with multiple voices shifting and relocating, always at a distance from her characters, rarely really sympathetically located in their reality, never really kind, always slightly satirical,

This is what makes the poetry so interesting. It is in the poetry – and not in the much more celebrated short stories or even the letters which are themselves a kind of performance – that, I feel, we actually encounter Mansfield unplugged.

In large part this is because so few of them were published in her lifetime. After her initial experience in London – where she would publish anything for anyone anywhere as a way of inserting herself into the not incredibly welcoming London literary scene – ‘She can write, damn her’ said Rupert Brooke of her NZ story ‘Mille’ – she published little or no poetry (4 out of 11 songs on this CD and those are early). She didn’t republish. Her poetry was only collected and published after her death – and some only defined as ‘poems’ by later editors, chiefly her husband John Middleton Murry, who ignored her wishes and published every single solitary scrap she had ever set to paper.

Mansfield did write poetry in her notebooks, privately, and poetry obviously meant more than – something more complicated than – literary production and professional advantage. The poems are immediate, responsive, fluid, and still taking shape – not drafts but pieces that were never meant to be worked up and broadcast. They are associated with her own very personal, developing sense of self. In 1915 she wrote ‘If I lived alone I would be very dependent on poetry’ (rather sad as she didn’t technically live alone, she lived with her not very supportive husband and sometimes it obviously felt like living alone). ‘I feel always trembling on the brink of poetry’ she wrote in 1916. And in 1921 she exclaimed ‘oh God! I am divided still. I am bad. I fail in my personal life. I lapse into impatience, temper, vanity & so I fail as thy priest. Perhaps poetry will help’.

Childhood is a recurrent theme in her poems – nostalgic, escapist, anti-modern in a manner that is a bit disconcerting in a so-called Modernist writer and hence very unlike her prose. Often, she expresses not just the memory of being a child but the wish to be so again. In her later stories Mansfield returns to her Wellington childhood but they are not lyrical; they are full of unease, conflicts, lapses, regrets and evasions of material and social life, in both the child and the adult world. But in her poetry this sharpness and complexity is not there – and neither is the deferring, the hiding, the masks. You can see this in the poem ‘To LHB’, written after her brother Leslie’s death in a First World War accident, where she begins:

Last night for the first time since you were dead

I walked with you, my brother, in a dream.

You can see this desire to regress to a place of safety in ‘There was a child once’. It’s in the restlessness of ‘Pic-Nic’. It’s in the lyricism of ‘Secret flowers’ where she asks ‘Is my love a star? A steady light?’

The poems which are, I feel, the most direct and to me heart-rending are those – late and unpublished in her lifetime – about her illness. She died at the age of 34 from tuberculosis. They are frighteningly clear-sighted. You hear her sharp voice in ‘The New Husband’, complaining of Murry’s neglect:

Some one came to me and said

Forget, forget that you’ve been wed

Who’s your man to leave you to be

Ill and cold in a far country

Who’s the husband – who’s the stone

Could leave a child like you alone?

Her illness meant that, at the end of her life, she lived in Europe, often in the south of France and the Italian Riviera, in hotels and lodgings. She writes, ‘I seem to spend half my life arriving in strange hotels – And asking if I may go to bed immediately’. There is a poignant contrast – and a leakage – between the picturesque settings and the grim reality of her illness. In ‘Sanary’, she looks out from ‘her little hot room’ to ‘the little boats caught in the web like flies’ and ‘a scent of dying mimosa flower/ Lay on the air but sweet – too sweet’. In ‘The Wounded Bird’ the speaker is:

In the wide bed

Under the green embroidered quilt

With flowers and leaves always in soft motion

[but] like a wounded bird resting on a pool.

Above: French for Rabbits perform 'The Wounded Bird' from the 2020 album Mansfield.

In ‘Sunset’, the ‘birds of shadow’ appear as a presage of death. In ‘Malade’ the speaker lies in her hotel room coughing –

The man in the room next to mine

Has got the same complaint as I

When I wake in the night I hear him turning

Then he coughs

And I cough ….

They are, she says ‘like two roosters calling to each other at false dawn’. I think this is my favourite because it manages to convey the awfulness of being ill with a rueful humour – and a sense of how you cast this terminal experience into literature – even if it’s just a matter of noticing syncopated coughing.

Above: Lawrence Arabia performs 'Malade' from the 2020 album Mansfield.

For a while when she was a young woman, Mansfield seriously intended to become a musician. She would really appreciate this project we are celebrating tonight. The skill, the respect, and the sympathy of these collaborations are delightful and wholly appropriate.

Professor Jane Stafford, Wellington, 20 February 2020.

Reproduced with kind permission of the author.

Mansfield is available on digital music platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music, and can be purchased as a CD (with the featured poems published in a booklet inside the CD) from our online shop and all good record stores.