PRINTING IN THE VICTORIAN ERA

- 22 June 2020

- Lara van der Raaij

Many of the pictures on display at Katherine Mansfield House & Garden are copies of Victorian prints.

During the Victorian era, printers experimented with a range of different techniques to reproduce original drawings. Developments in printing techniques, including engraving and lithography, allowed for mass printing. Prints made owning artwork more affordable, which made prints popular with middle-class Victorians who could not afford to buy original art. Engraving and lithography were also used to reproduce art in newspapers and books.

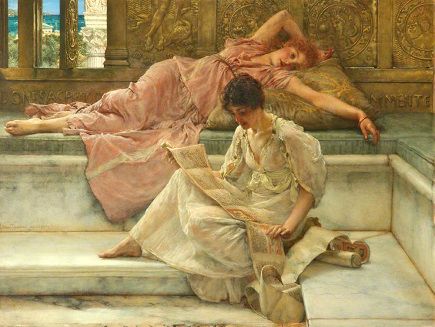

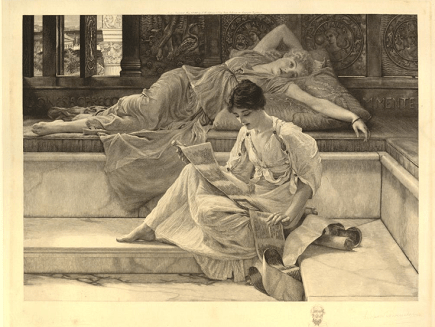

It was common for partnerships to be formed between artists and engravers to create prints. Successful partnerships were formed when the artist and engraver had compatible styles. For example, the clean lines of Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s painting style were matched by his engraver Leopold Lowenstam. (Alma-Tadema is the artist of 'Her Eyes are with Her Thoughts and They are Far Away', a copy of which is displayed at Katherine Mansfield House & Garden and explored in a previous blog post). Alma-Tadema and Lowenstam famously disliked each other but continued their partnership due to its financial benefits. The more popular the artist, the higher demand for quality prints. The artist also made money from prints without creating additional original artworks.

Images: The painting Favourite Poet by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888) and an etching of Favourite Poet by Leopold Lowenstam (1889). Courtesy of Art UK and The British Museum.

The popular methods of mark-making used in engraving and lithography have come to define the graphic style of everyday Victorian life. Below are brief descriptions of the techniques used in engraving and lithography and the resulting styles of each technique.

Wood Engraving

The process of wood-block printing involves copying a drawing onto the end grain of a wood block. The block is then cut into by an engraver according to the areas which will not be printed. Printing ink collects in the cut areas.

Engraving tools typically create fine strokes, which are built up to create the darker areas of the final print. From afar, the fine nature of each incision creates the appearance of smooth shading.

Wood engraving was typically used for monochrome prints. In order to create a multi-coloured wood block print, separate blocks are required for each colour. Each block is then printed on top of the other in layers.

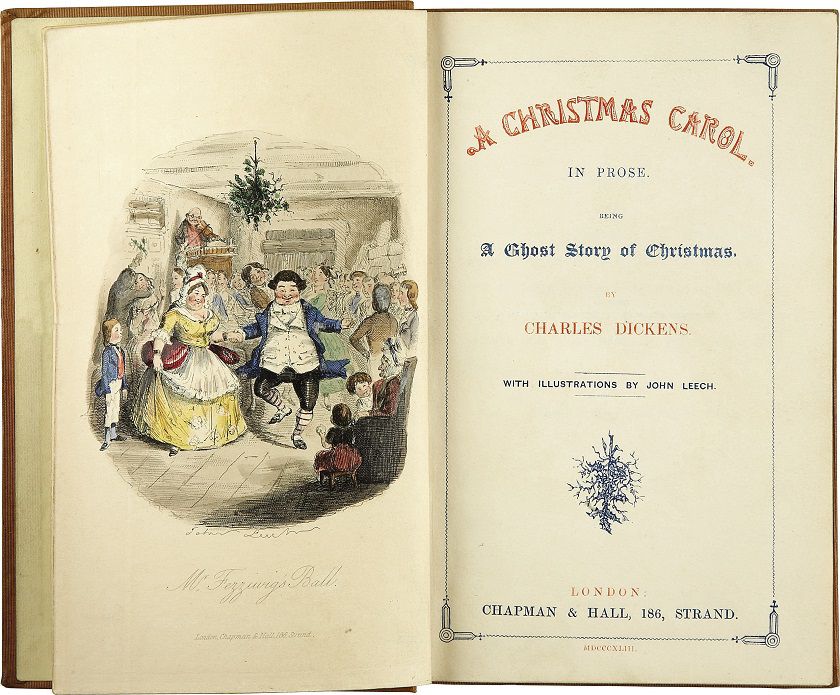

Alternatively, monochrome prints were hand-coloured with watercolour washes. A famous example are the original illustrations for Charles Dicken’s ‘A Christmas Carol’ by John Leech. However, this was a time consuming and expensive process, losing popularity after 1830.

Image: The frontispiece of A Christmas Carol with handcoloured illustrations by John Leech (1843). Courtesy of Wikimedia.

Lithography

Lithography gained popularity from the mid-19th century as a cheaper and more versatile alternative to wood engraving. The process was discovered accidentally around 1796 by a Bavarian playwright, Alois Senefelder.

Lithography involves drawing the original image with a greasy pencil or ink onto a porous material. Limestone was originally used as the print surface, but metal plates could also be used. The greasy drawn image is fixed to the plate with an acid bath.

In order to print, the plate is first moistened, then inked. The greasy image repels the water but absorbs the ink. The plate can then be used to print.

Unlike wood block printing, in lithography the image does not need to be inverted on the plate. The areas were the greased pencil is applied are the dark regions of the final print. In woodblock printing, the areas cut are not covered with ink, becoming the ‘white’ regions of the final print.

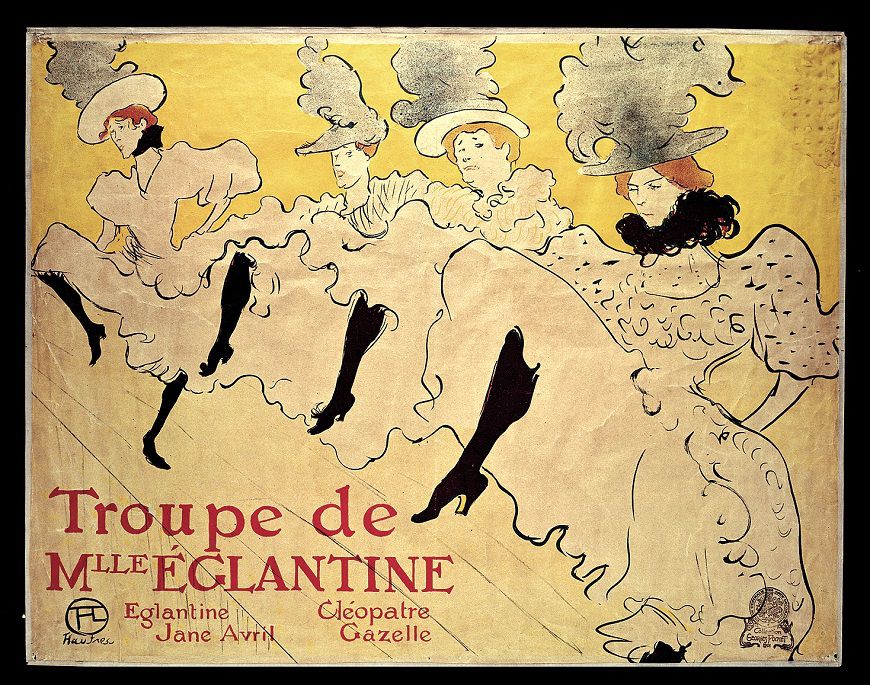

Lithographs were also not limited to the fine stokes created by engraving tools, allowing for more versatile marks to be made. Improvements in printing technology then made it possible to add colour and increase print runs, revolutionising advertising.

Image: La Troupe de Mademoiselle Eglantine, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1895). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Further Reading

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 'Lithograph' (process illustrated with GIFs) and 'Lithography in the Nineteenth Century'

Victorian Illustrators: From Sketch to Print, 'Early Methods and Technologies'

The Victorian Web, 'The Technologies of Nineteenth-Century Illustration: Woodblock Engraving, Steel Engraving, and Other Processes'

Homes & Antiques, 'The Knowledge: Rupert Maas on Victorian engravings'