This exhibition ran from 14 December 2021 to 13 March 2022 and explored the important role music and musicians played in Katherine Mansfield’s life, particularly as a teenager and in her development as a writer.

Exhibition text by Cherie Jacobson (Director, Katherine Mansfield House & Garden). With special thanks to Martin Griffiths, Bethany Gwynne, Roger Joyce and Minette Parker. Exhibition photographs by Stephen A'Court.

Introduction

“I’d rather be with musical people than any others … they’re mine, really.” Katherine Mansfield in a journal entry, 1914

This exhibition explores the important role music and musicians played in Katherine Mansfield’s life, particularly as a teenager and in her development as a writer. From an early age, music and performance were part of Katherine’s family life. Before gramophones and radio became commonly available, live music was a key form of entertainment. Like many young women in their social circle, Katherine and her sisters had music lessons. Katherine learned the piano, then the cello. In April 1907, Katherine’s mother held an ‘At Home’ which was reported in the social column of the Wairarapa Daily Times as “the social event of the week.”[1] The columnist noted that the house on Fitzherbert Terrace had a dedicated music room, with no furniture except for a piano and some chairs, and that “a feature of the tea was the delightful music from the daughters of the house.” Katherine’s eldest sister, Vera, played the piano, Charlotte sang, and Katherine played the cello – “an unusual instrument for a girl to master.”

Through her piano teacher, Robert Parker, and cello teacher, Thomas Trowell, Katherine was well connected to the music scene in Wellington and for a time she aspired to be a professional cellist. Although she stopped playing the cello in 1909 aged 20, the discipline required to become a skilled musician and the constant striving for technical mastery remained with her as she turned her focus to developing her craft as a writer. As an adult Katherine was known to play the guitar and sing in a “high, pure soprano.”[2] Throughout her life she loved to attend concerts and in her final months music was an important part of the daily routine at the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man.

Music often featured in Katherine’s stories and even influenced her writing style. In her last completed story, ‘The Canary’, a woman mourns the death of her beloved canary, who “used to hop, hop, hop from one perch to another, tap against the bars as if to attract my attention, sip a little water just as a professional singer might, and then break into a song so exquisite that I had to put my needle down to listen to him.”

The Trowell Family

“You have shown me that there is something so immeasurably higher and greater than I had ever realised before in Music – and therefore, too, in Life.” Katherine Mansfield in a letter to Thomas Trowell (Senior), September 1907

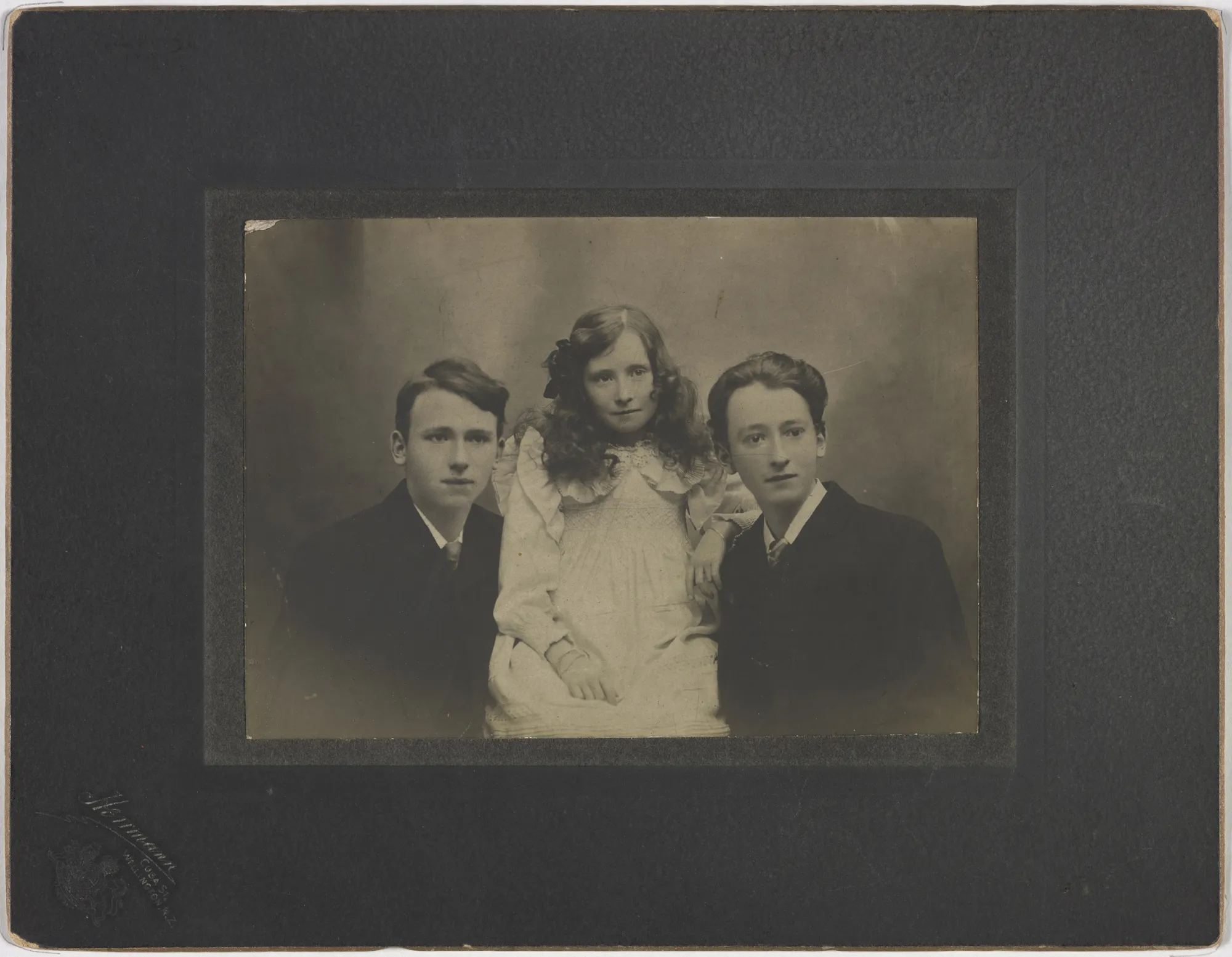

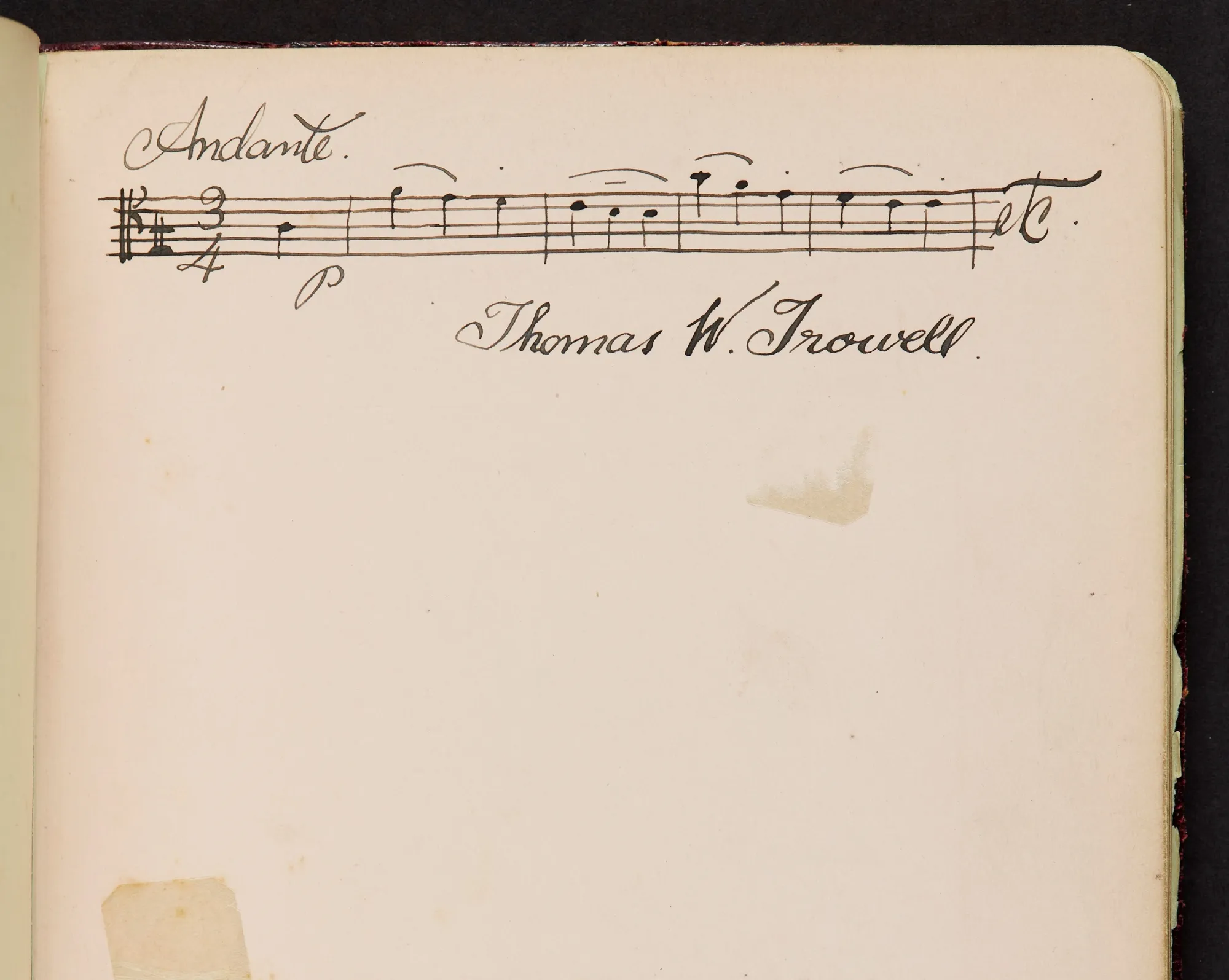

The first instrument Katherine Mansfield learned to play was the piano, but in 1901 she began to take cello lessons from Thomas Luigi Trowell (1859-1945). One of Trowell’s twin sons, also named Thomas, was a year older than Katherine and already showing great promise as a cellist himself. Katherine was captivated by the teenage Thomas’s looks and talent. Whether her decision to learn the cello was influenced by a crush on Thomas or not, Katherine quickly became a dedicated student and music took on a new significance in her life.

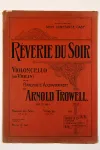

Katherine and Thomas stayed in contact from 1903, when Katherine began attending Queen’s College in London and Thomas moved to Europe to further his musical training. Katherine even travelled to Brussells with her aunt and sisters in March 1906 to attend a concert given by Thomas at the Salle de la Grande Harmonie. By this time Thomas had begun to use the name ‘Arnold Trowell’ as his stage name. Katherine had her own plans of becoming a professional cellist, but in April 1906 she wrote to her cousin that her father was “greatly opposed to my wish to be a professional ‘cellist or to take up the ‘cello to any great extent – so my hope for a musical career is absolutely gone.” Katherine continued to play the cello, however, and after returning to Wellington in December 1906 played with Thomas Trowell (senior) at private gatherings and at least one public concert.

"August 27th. A happy day. I have spent a perfect day. Never have I loved Mr Trowell so much, or felt so in accord with him, and my ‘cello expressing everything. This morning we played Weber’s Trio – tragic, fiercely dramatic, full of rhythm and accent and close shade." Katherine Mansfield in a diary entry, 1907

In April 1908, Mr and Mrs Trowell and their daughter Dolly moved to London to be reunited with the twins Thomas and Garnet. A few months later Katherine finally convinced her parents to let her return to London and she quickly began spending time at the Trowell’s new home. Despite having written him passionate letters from Wellington, it was now clear that the young Thomas did not share Katherine’s feelings and had begun a relationship with one of her friends from Queen’s College. Katherine shifted her attention to Garnet and the two began a relationship of their own.

Unfortunately, Katherine’s association with the Trowell family came to a messy end in 1909. She sold her cello and had no further contact with the Trowells. Her love of music remained, however, and just weeks before her death at the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in 1923, she wrote to her friend Ida Baker and asked her to urgently send a book of exercises for teaching the cello.

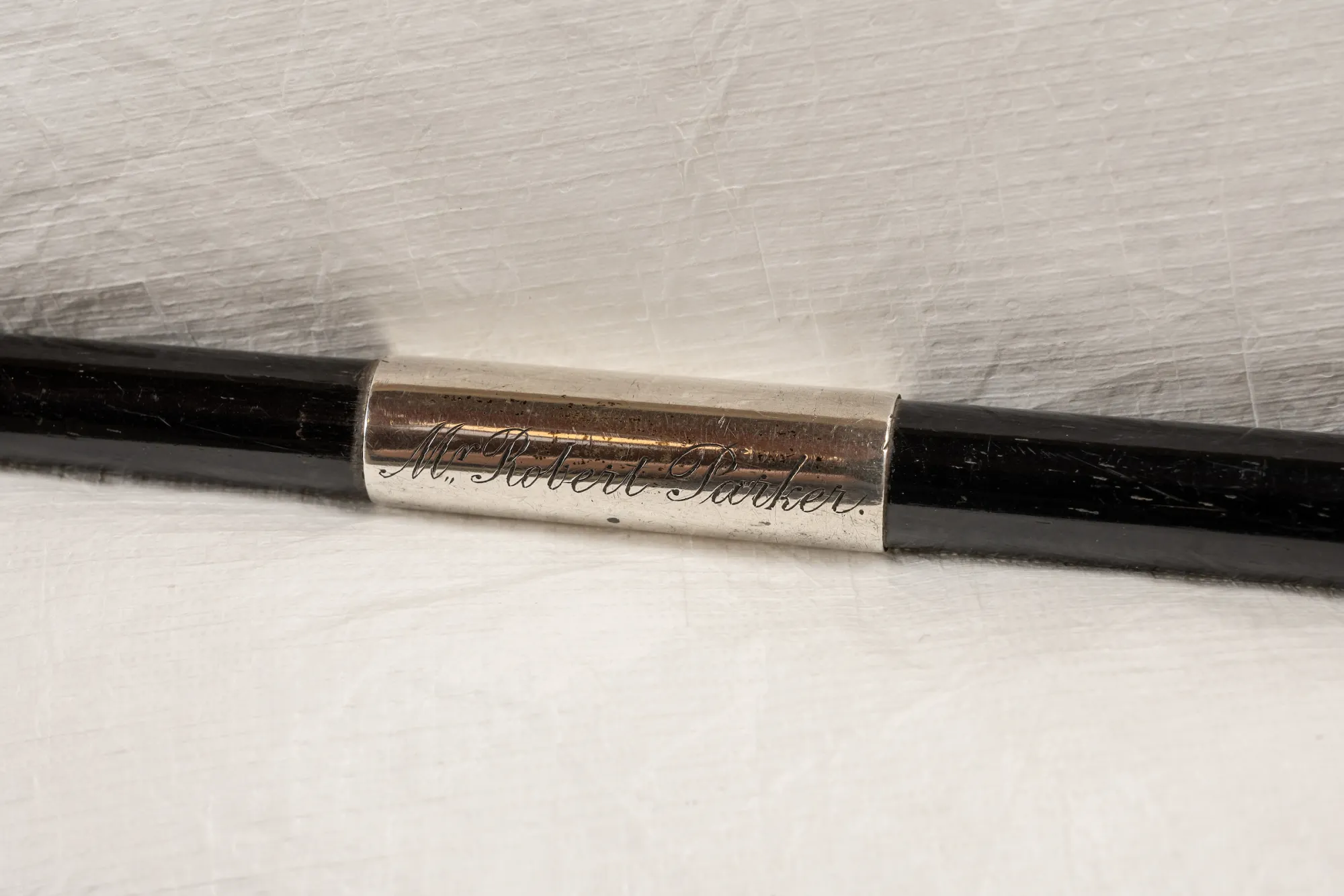

Robert Parker

Mr. Bullen’s drawing-room is as quiet as a cave. The windows are closed, the blinds half-pulled, and she is not late. The-girl-before-her has just started playing MacDowell’s ‘To an Iceberg.’ Mr. Bullen looks over at her and half smiles.

“Sit down,” he says. “Sit over there in the sofa corner, little lady.”

How funny he is. He doesn’t exactly laugh at you … but there is just something … Oh, how peaceful it is here. She likes this room. It smells of art serge and stale smoke and chrysanthemums … there is a big vase of them on the mantelpiece behind the pale photograph of Rubinstein … à mon ami Robert Bullen … Over the black glittering piano hangs ‘Solitude’ – a dark tragic woman draped in white, sitting on a rock, her knees crossed, her chin on her hands.

Parker also taught Katherine’s father piano. Her uncle, Frederick Valentine Waters, was a very active baritone singer and knew Parker well. Parker conducted him in the Wellington Liedertafel (male voice choir) and other performances and festivals.

'The Chorus Girl and the Tariff'

In November 1909 a piece by ‘Katherine Mansfield’ was published by the National Monthly Magazine in Buffalo, New York. ‘The Chorus Girl and the Tariff’ is told from the point of view of a world-weary American chorus girl who is the “head spear carrier in Err & Klawlingers Mugnaficent Merry-Makers.”

The unnamed chorus girl describes life in a travelling show – the early starts and late nights, bad meals, the pay rates and increasing taxes, the sections of the chorus from ‘regulars’ to ‘shows’, and the personal lives of some of the girls she works with. She explains that most chorus girls don’t get married, partly because they don’t stay in one place long enough to meet anyone and partly because the behaviour of a few chorus girls gives all of them a bad reputation. By the end of the piece, we know that this chorus girl has a good heart – she hasn’t had a day off in a long time because she gives her days off to other girls who need them more. In spite of her complaints, it seems unlikely she’ll have a career change anytime soon.

In an article published in the most recent Katherine Mansfield Studies journal, Martin Griffiths explores whether this story, with its turn-of-the-century American vernacular and seemingly deep knowledge of life as a chorus girl, could in fact be by the New Zealand-born Katherine Mansfield. He ultimately finds that “Mansfield is as good a candidate as any, and aspects of subject, biographical opportunity and stylistic preference are valid supporting evidence for attribution to the New Zealand-born author.” Two recent articles provide more information on Griffiths' find and invite debate, see an article from the New Zealand Herald here and an article from Newsroom here.

By November 1909, Katherine had been back living in London for just over a year. She had sung in the chorus of the Moody Manners Opera Company for a few weeks in March 1909 while travelling with Garnet Trowell. Around this time, she also acted in skits as paid entertainment at West End society hostesses’ soirées. She frequently attended all kinds of stage performances and had met various travelling performers in Wellington and London, such as international singing star Clara Butt and pianist Teresa Carreño. All these experiences could have contributed to her knowledge of the life of a chorus girl, which was also a subject of interest to the general public. Even newspapers in New Zealand carried articles about international scandals involving chorus girls, the salaries of chorus girls in America and Australia and chorus girls needing good teeth for appealing smiles.

Katherine Mansfield: Lyricist?

The lyrics of the two songs were originally written as poems by Katherine during the family’s sea voyage to England in January 1903. Vera set the poems to music soon after. Their father Harold Beauchamp, who enjoyed music and was Chair of the New Zealand Piano Company, almost certainly paid for the songs to be published. He must have been very proud of his daughters’ efforts as a newspaper article in August 1904 notes that the two songs were performed by Harold’s brother-in-law, who was a well-known local singer, at a dinner for the Wellington Harbour Board. Harold had been Chair of the Wellington Harbour Board from 1900 to 1903.

The songs are for voice and piano and are in the tradition of parlour music, which was intended to be performed in the parlour or drawing room of a private house, usually by amateur pianists and singers to entertain family or guests. Parlour music fell out of fashion once phonographs and gramophones (early forms of record players) and radio became common.

In Katherine’s story ‘The Garden Party’, Jose, one of the Sheridan sisters, arranges for the piano to be moved and practices a song in case she is asked to perform during the garden party the family is hosting.

She turned to Meg. “I want to hear what the piano sounds like, just in case I’m asked to sing this afternoon. Let’s try over ‘This Life is Weary.’”

Pom! Ta-ta-ta Tee-ta! The piano burst out so passionately that Jose’s face changed. She clasped her hands. She looked mournfully and enigmatically at her mother and Laura as they came in.

This Life is Wee-ary,

A Tear – a Sigh.

A Love that Chan-ges,

This Life is Wee-ary,

A Tear – a Sigh.

A Love that Chan-ges,

And then . . . Goodbye!

But at the word ‘Goodbye,’ and although the piano sounded more desperate than ever, her face broke into a brilliant, dreadfully unsympathetic smile.

“Aren’t I in good voice, mummy?” she beamed.

Composing Prose

“In ‘Miss Brill’ I choose not only the length of every sentence, but even the sound of every sentence. I choose the rise and fall of every paragraph to fit her, and to fit her on that day at that very moment. After I’d written it I read it aloud – numbers of times – just as one would play over a musical composition – trying to get it nearer and nearer to the expression of Miss Brill – until it fitted her.” Katherine Mansfield in a letter to her brother-in-law Richard Murry, 17 January 1921.

Katherine Mansfield’s love of music and her musical training significantly influenced her writing. Music, instruments and musicians frequently appear in her stories, with some stories entirely focused on them. Mr Reginald Peacock in ‘Mr Reginald Peacock’s Day’ (1917) is a self-important singer and private singing teacher, while in ‘The Singing Lesson’ (1920) the love life of the singing teacher at a girls’ school dictates the mood of the lesson. The music of the natural world can also be found throughout Katherine’s works, such as birdsong and the sounds of the wind and the sea.

Katherine’s writing techniques and her approach to the craft of writing owe a lot to her musical training. Scholar Delia da Sousa Correa uses ‘At the Bay’ as an example of a story that “makes little direct reference to music, but is highly musical in its structure and language.”[5] She compares different sections of the story to musical movements – the description of the early morning landscape is a calm, opening overture; later, the children’s card game “a comic-macabre scherzo, a virtuoso performance where snippets of dialogue and description echo the slapping of cards on the table in a frenetic crescendo.”[6] The rhythm and comic timing of Katherine’s stories, the way sounds are used to create texture and the lyricism of her writing all contribute to musical readings of many of her works.

The discipline of seriously learning an instrument and practicing for performance as a young woman set a strong foundation for Katherine’s dedication to her craft as a writer. She worked at it daily, when her health allowed, and was constantly striving to improve. A 1918 journal entry shows she consciously related the technical skill of playing music to her writing:

Whenever I have a conversation about Art which is more or less interesting I begin to wish to God I could destroy all that I have written and start again: it all seems like so many ‘false starts’. Musically speaking, it is not—has not been—In the middle of the note—you know what I mean? When, on a cold morning perhaps, you’ve been playing and it has sounded all right—until suddenly, you realize you are warm—you have only just begun to play.

In a notebook from 1916, at the end of a paragraph describing her struggle to write on that particular day, Katherine drew sketches of a cello and a group of musicians, along with some musical notations. A literal illustration that music was never far from her mind, particularly when writing.

Notes

[1] 'Life in the City', Wairarapa Daily Times, 30 April 1907, p.3. You can read the full article here.

[2] Ida Baker, The Memories of LM (London: Michael Joseph, 1971), p.233.

[3] ‘Obituary Mr Robert Parker Veteran Musician’, Evening Post, 20 February 1937, p.11. You can read the full obituary online here.

[4] 'After Twenty-One Years', Dominion, 18 December 1912, p.6. You can read the full article here.

[5] and [6] Delia da Sousa Correa, ‘Katherine Mansfield and Music: Nineteenth Century Echoes’, in Celebrating Katherine Mansfield: A Centenary Volume of Essays (London: Palgrave Macmillian, 2011), p.84.

© Katherine Mansfield House & Garden 2021.

Please note that all text is copyright Katherine Mansfield House & Garden unless otherwise stated. Please contact us for permission to use images for anything other than your own research purposes, such as publication online or in print. Images of items held in the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library are subject to the Library's terms of use - follow the link for each item via its collection reference number in the image caption to learn more.