This exhibition ran from 23 March to 26 June 2022 and was curated by costumier and fashion and textile historian Leimomi Oakes (The Dreamstress). It showcased selected textiles from the collection of Katherine Mansfield House & Garden, highlighting the techniques used to create them and offering a glimpse into the world of their makers.

Exhibition text by Leimomi Oakes. Exhibition photographs by Stephen A'Court.

Introduction

Katherine Mansfield loved fashion and textiles. She carefully chose a unique wardrobe which fit her own artistic taste and suited her carefully built persona of modern bohemian writer. She vehemently declared “I am a very MODERN woman. I like life in my clothes.” She felt that “Clothes ought to be a joy to the artistic eye – a silent reflex of the soul…”

Some people appreciated Mansfield’s taste; others weren’t quite so impressed. Her brother-in-law Richard Murry described her as “a head-turner. The mode from Paris; the brown velvet jacket with silver buttons, the short skirt, the coloured stockings, the Spanish-Japanese hair-do, the high heels, the immaculate turnout.” Virginia Woolf, on the other hand, was “a little shocked by her commonness at first sight: lines so hard and cheap.”

While opinions on her personal taste may have been divided, her precise grasp of clothing description in her writing is undeniably exquisite. Her stories are full of mentions of garments which set the scene, move the plot forward, and give us an insight into her characters.

The "very nice stewardess" in ‘The Voyage’ “dressed all in blue and her collars and cuffs were fastened with large brass buttons” taking “a long mournful look at grandma’s blackness and Fenella’s black coat and skirt, black blouse, and hat with a crepe rose” tells us both about the reason for Fenella’s trip, and her fascination with the novelty of the overnight ferry. Laura’s borrowed hat in ‘The Garden Party’ “trimmed with gold daisies, and a long black velvet ribbon,” “quite Spanish…so striking” shows the dichotomy of life and death: the daisies the epitome of youth, the ribbon alluding to mourning dress. The shoppers in ‘The Tiredness of Rosabel’, the “awful woman in the grey mackintosh who wanted a trimmed motor cap – ‘something purple with something rosy each side’” contrasting with the girl with red hair and eyes “the colour of that green ribbon shot with gold they had got from Paris last week”, who turns down every other hat until she sees the one “rather large, soft, with a great, curled feather and a black velvet rose, nothing else.” Each description helps to create a perfect scene, each detail carefully considered, allowing us to step into the story and observe the character.

In a similar way, looking closely at the details of the garments in this exhibition gives us an insight into when they were made, who they were made by and under what conditions, why they were made, and how they were made. Each garment tells its own story – ‘meet the making’ and get a glimpse into the world of the makers of these historical treasures.

Hidden Layers

Edwardian undergarments, despite being hidden under layers of outer clothes, feature lavish amounts of decorative trimmings. The profusion of lace, tucks, and ruffles was made possible by technological advances, and an army of poorly paid working women sewing in sweatshops or doing piecework from home.

Technological advances included specialised sewing machines that sewed pintucks and other decorative features and machines that could embroider and weave a variety of laces. Piecework was handwork done from home. It allowed women to earn an income around childcare and taking care of the household. Piecework was paid per completed item, so the faster a woman could sew, the more she earned. The more skilled the work, the higher the pay. Even so, piecework was notoriously badly paid. Factory workers were more likely to earn a guaranteed wage, but faced long, inflexible hours and dangerous working conditions.

This petticoat features broderie anglaise ruffles attached to the skirt with zig-zagged gathers. Broderie anglaise is a type of embroidery combining satin stitches and holes worked in the fabric, with the edges finished with overcast or buttonhole stitching. Broderie anglaise was always done by hand: each stitch carefully placed by an expert needlewoman, usually one doing it as piecework from home. The finished embroidered ruffle or motif might be sent to a factory to be assembled into a petticoat or sold at a shop for a dressmaker to make up.

In addition to its fancy ruffles, this petticoat has a very practical secret: a large, square pocket placed halfway up the skirt. In-period mentions in newspapers suggest such pockets might be used to carry stashes of money. Health guides for women doing war work during the First World War suggest a more practical, but less publicly printable, use for the pockets. They were the perfect place to keep sanitary products, including the newly available disposable pads of paper and cotton.

The corset cover paired with the petticoat is slightly later in make, and much more basic in its construction. The filet lace yoke might have been done as piecework, or made at home, following instructions from one of the popular needlework magazines. The corset cover features simple but clever construction. It is a rectangle of fabric with triangular darts taken at each side to shape it in to the waist. Gathers below the bust help create the fashionable full, low bust silhouette of the 1910s. A drawstring channel at the waist means the corset cover is somewhat adjustable: a helpful consideration with ready-made garments.

Re-Fashioning Fashion

The low wages paid to seamstresses and dressmakers in the 19th and early 20th century meant that the fabric a garment was made from, particularly if it was a luxury fabric like silk, was the most expensive part of a dress. To save money, women often re-made garments from season to season: updating the cut and trims to match the latest fashion. Garments with full skirts or other large expanses of fabric could be completely unpicked, re-cut, and made into new garments.

Such re-fashions were widely practiced at almost all levels of society. Examples of gowns made from 18th century fabric by demi-couture houses and high-end dressmakers show that even the extremely wealthy sometimes took advantage of the durability and beauty of older fabrics. Minor re-makes could be done at home even by a fairly inexperienced seamstress. More elaborate re-fashions might involve taking the original garment to a professional dressmaker. Even a complete re-make by a professional dressmaker was cheaper than a similar garment of new fabric.

This dress is a fascinating example of fashionable re-making which takes into account the taste of the client. It appears to be a late 19th century garment which was altered in the mid-1910s to suit the styles of that era. It may also have had a further re-make in the 1930s. It is difficult to precisely date the dress both because of the re-making, and because it appears to have been made, or at least re-fashioned, for an older woman. The overall cut of the dress is quite conservative, but the garment includes fashionable design elements from each era of its life, such as the jet beading, typical of 1880s and 1890s garments, and the quirky pockets, a common feature of 1910s fashion. It suggests a client who wanted to acknowledge the new styles and changing fashion trends, without completely relinquishing a silhouette that she was comfortable with, and details from earlier styles that she had enjoyed.

It is easy to see why the fabric of this dress was cherished and re-used. The black silk damask, with its motifs of circular swirls and garlands of tiny flowers, is almost as bright and lush today as when it was made, over 120 years ago.

The workmanship of the re-make does justice to the quality of the fabric, suggesting it was done by a professional dressmaker.

Machines, Makers and Ready Made

William Lee’s invention of the stocking frame in 1589 revolutionised the textile industry. The machine used wire needles to imitate the motions of hand-knitting, producing fabric hundreds of times faster than a hand-knitter could. It helped to spark the Industrial Revolution and inspired other inventors to create machines to replace hand processes. By Mansfield’s day, machine-made garments dominated the wardrobes of the Western world, and manufacturing had lost its novelty.

This Edwardian blouse, with its profusion of pintucks and lace insertion, is an excellent example of the cachet of handmade garments in the Edwardian Era. The blouse features dozens of rows of tiny handsewn pintucks interspersed with handmade valenciennes lace, made by weaving and twisting threads on bobbins around each other to form a pattern. The lace has been joined to the blouse fabric with tiny whip stitches. Each of these techniques required skill, time, and exceptional concentration. A small red ‘HAND MADE’ label sewn into the peplum advertises the human touch that went into the blouse.

Like Petticoat KMBS0900 and Corset Cover KMBS0594 this blouse may have been done as piecework. It shows signs of remaking: the neckline appears to have been cut down from a high early Edwardian neckline to the wider neckline fashionable in the 1910s.

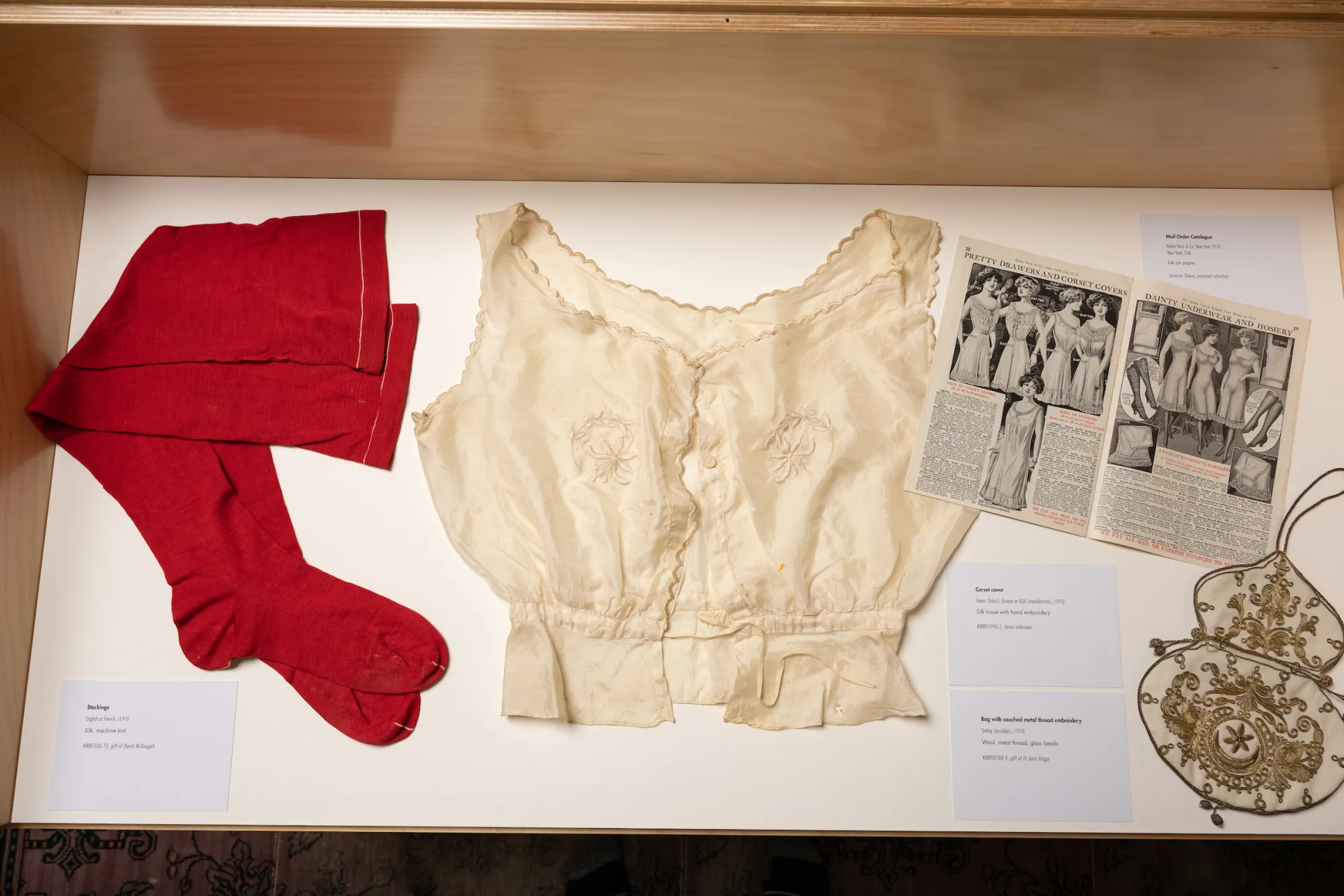

While the blouse is handmade, these red silk stockings are manufactured and are a direct result of Lee’s invention. Lee’s Frame was originally designed to knit stockings. The thriving industry that arose around stocking making using Lee’s frame in the 17th century and onward made wool and textiles the backbone of the English economy. The desire to protect this industry in the face of competition from cotton textiles coming from India was one of the factors that contributed to English expansion into the Indian Subcontinent under the British East India Company, and to British exploration in the Pacific in the 18th century.

The child’s cape combines machine and hand elements. The floral chain-stitch embroidery was done by machine to fit the dimensions of the finished cape. Once the fabric was embroidered the cape was assembled by hand: padding was attached, the lining slipstitched in, binding was sewn round the edge, and trim was applied. The twisted passementerie trim was woven on a specialised loom. Look closely at the gathered ribbon that frames the neck and is curled along the front edge and you can see that two lines of gathering threads were woven into the ribbon. All the seamstress assembling the cape had to do was pull them to gather in the ribbon, and stitch it on.

Edwardian Details

The Edwardian Era (1901-1910) was a decade of exuberance. Edward VII, a king notorious for his love of parties and fun, and his glamorous wife Alexandra replaced the staid Victoria, confined forever in black mourning for her long-dead husband. Fashion and society responded by breaking out in a rash of gaiety. Pastels, puffs, ruffles and lace dominated Edwardian fashions for women. Mansfield herself rejected these clothes, leaving the “fair and fluffy Edwardian ideal” to her sisters, and opting for a sleek modern approach. Edwardian clothes, however, appear as ghosts in her stories, strolling across the lawn in ‘The Garden Party’, and in mentions of “ruffled white dressing gowns” and “camisoles with ribbons on the shoulder” in ‘At the Bay’.

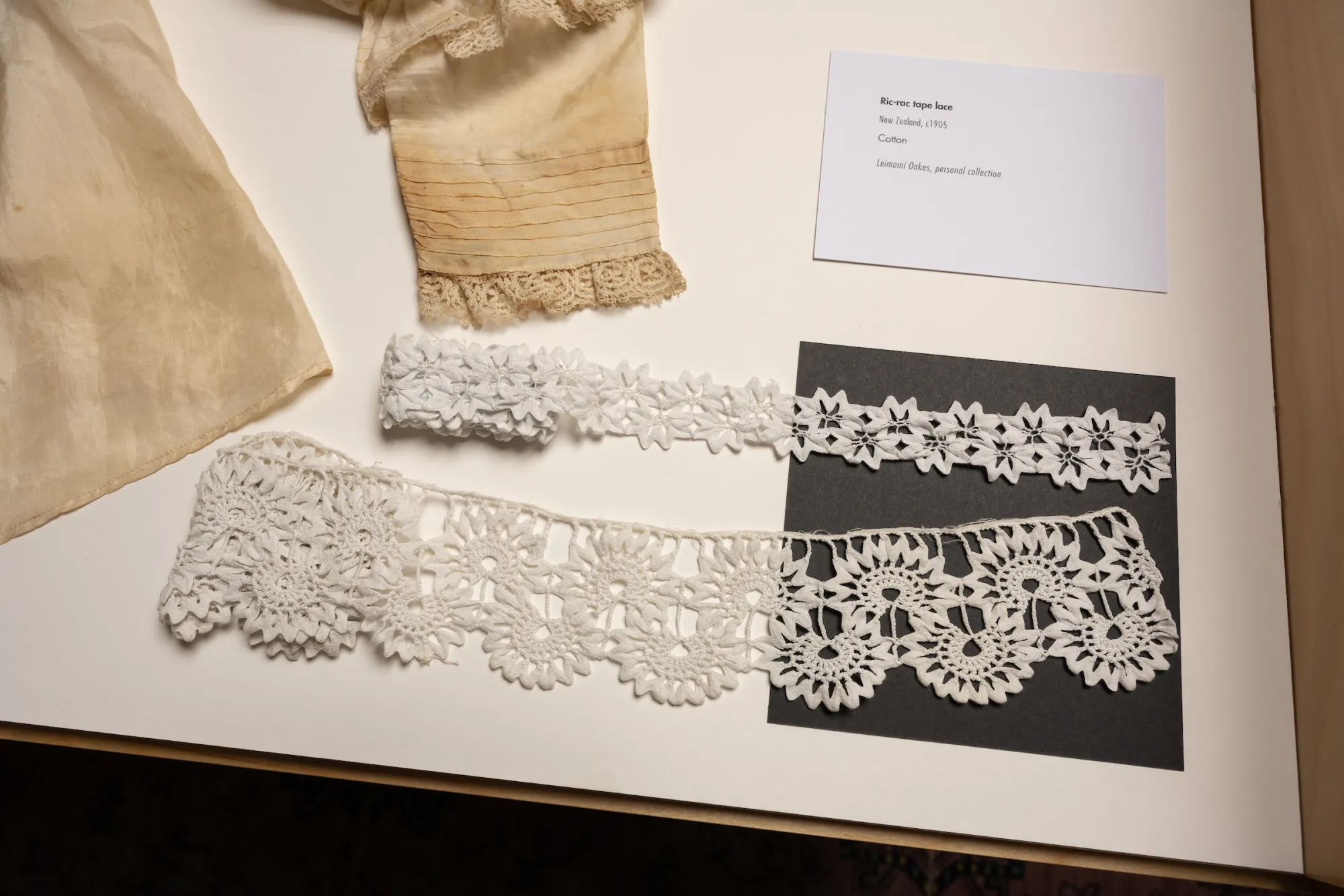

Images above: Silk and lace bodice, 1902. Cotton, silk tissue, hand and machine-made lace, silk ric-rac trim, baleen, shell buttons. KMBS1096 – Donor unknown; Examples of ric-rac tape lace, c1905. From the personal collection of Leimomi Oakes.

This silk and lace bodice, with its profusion of smocking, tucks, lace insertion, puffs, and ruffles, epitomises the Edwardian taste for embellishment. The high collar, yoke, double-layer puffed sleeves, and loose front that could be drawn up to create the ‘pigeon breasted’ silhouette are all typical of the styles of 1902-1905.

The high collar is made of bobbin lace, trimmed with silk ric-rac, and supported by short lengths of whalebone in narrow casings, creating the high neckline made fashionable by Queen Alexandra, who used it to hide a scar on her neck. While we often associate ric-rac with mid-20th century fashion, it dates back to at least the 1840s. In addition to appearing as applied trim, it was also shaped into lace and used to trim petticoats and other undergarments.

The yoke of the bodice is smocked, a technique adapted from traditional farmers’ working shirts (smocks) in England. In smocking, fabric is finely pleated and the pleats are held in place by simple embroidery stitches worked on the outside of the garment. Each stitch catches only one pleat, forming a flexible fabric that moves and gives around the body. Smocking was first adopted by the Arts & Crafts and Aesthetic movements, which rejected the confines of fashionable Victorian dress and looked to traditional crafts for alternatives. It gradually became conventionally fashionable, influenced by stores like Liberty of London who sold garments that blended fashionable styles and counter-culture techniques.

As the Edwardian era transitioned into the 1910s, fashion became sleeker and more restrained. This black lace over-jacket shows the transition of styles, balancing a decadent fabric with a simpler silhouette. It is made from black silk bobbinet appliquéd with black satin leaf cut-outs and black cord trim. The bobbinet was made by machine, a technique invented in 1814, and the satin appliqué work would have been done by a skilled machinist.

The Global Fashion Trade

The 19th century saw a massive increase in the speed of transport, with steamships and trains reducing journeys that had taken months by sail to weeks, and weeks by carriage to days or hours. Faster transport resulted in a massive increase in worldwide commerce, anticipating modern day globalisation. Goods travelled around the world, and clothes from far-flung locales were particularly in demand.

The average upper-middle-class Wellingtonian might wear chemises made in New Zealand of fabric woven in England from American cotton, corsets made in Belgium, straw hats from Italy, dresses of Chinese silk and Indian muslin. Mansfield carried fans from Japan and wore shawls from China, peasant costumes from the Ukraine, stockings from France, and pounamu earrings and a hei tiki from here in New Zealand. The characters in her stories wear equally international clothes. In ‘The Garden Party’ Jose comes down to breakfast “in a silk petticoat and a kimono jacket.” Mrs Norman Knight’s “amusing orange coat with a procession of black monkeys round the hem and up the front” in ‘Bliss’ was probably made in India.

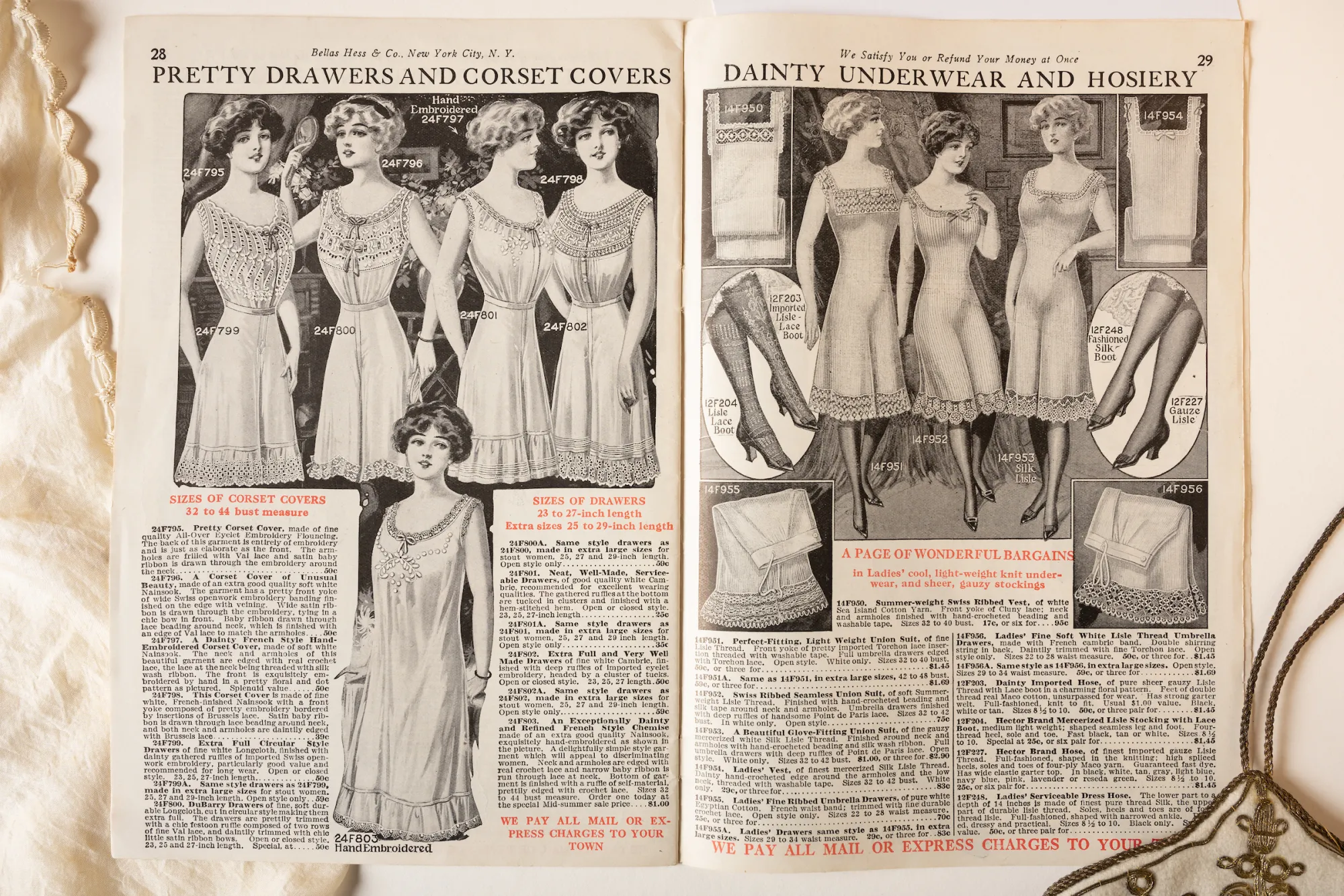

Images above: A display case containing the red stockings discussed in the 'Machines, Makers and Ready Made' section; Corset cover (made in Europe or the USA), c1910. Japanese silk tissue. KMBS1096.1 - Donor unknown; the open pages of a mail order catalogue from Bellas Hess & Co (New York),1912. From the personal collection of Leimomi Oakes; Bag (possibly Turkish), c1910 - further details accompany the photo below.

The textile collection at Katherine Mansfield House & Garden is as diverse as Mansfield’s wardrobe. The origins of some of the items are impossible to identify. The petticoats and corset covers could have been made in New Zealand or Australia, or anywhere in Europe, the British Isles, America, or Canada: materials and making techniques were so universal. In other cases, we can make an educated guess.

The small ivory bag with gold embroidery is typical of items made in Turkey and other parts of the former Ottoman Empire for the tourist market. The bag features teardrop shaped ‘boteh’ (sometimes known as paisley) motifs in gold couching. The boteh motif originated in Persia (now Iran) and spread across the Near East to India. It then spread to the West via the trade in Kashmiri shawls in the early 19th century. These shawls were extremely desirable, and extremely expensive, so various European textile centres, including Paisley, in Scotland, began making imitations, leading to the modern name for the motif. The West associated the boteh motif with the cachet of Kashmiri shawls, and the Islamic world appreciated that it was non-figurative. This bag thus appealed to both markets.

Couching is an embroidery technique where a thick thread is laid down in a decorative pattern, and then secured in place with small stitches. The couching on this bag is done in metal thread, which is made by rolling thread over paper thin metal. If this thread was pulled through the fabric, as in standard embroidery, the metal would be stripped off.

Curator Talk

You can watch a wonderful talk Leimomi gave about the exhibition here. The talk is approximately 45 minutes in duration, plus a Q&A session. Please note that at the beginning when Leimomi is introduced the visual quality is not optimal, but once Leimomi starts screen sharing her slides it's perfect.

© Leimomi Oakes and Katherine Mansfield House & Garden 2022. Please contact Katherine Mansfield House & Garden for permission to use the images for anything other than your own research purposes, such as publication online or in print.